In the arenas that shape international public opinion, Japanese are frequently charged with being unusually unwilling to admit the harm that their wartime state policies caused to others. Yet making this accusation requires looking comparatively; are the Japanese really so much worse at confronting their own ugly past actions than everyone else? Regrettably, such comparisons show that most governments and societies find this an extremely difficult task.

And, just as in Japan, some individuals tackle this question in their own work precisely because they are troubled by their leaders’ lack of self-criticism. Boston-based visual artist Eleanor Rubin has explored many of the same problems as has Tomiyama in her artistic practice. http://ellyrubin.com/index.html

Rubin highlights the question of the social responsibility of the artist in her responses to the Vietnam War and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. And, although she is twenty years younger than Tomiyama, the two women encountered feminism at about the same time, with a similar impact on their art. Both artists focus on the costs of war to individuals, and both believe that art has the power to move viewers to “re-envision” official versions of history. For both, the legacies of World War II, the implications of racial contempt, and the ugly side of nationalism have shaped their personal histories and the direction of their work. Moreover, both Tomiyama and Rubin value active engagement with social movements as a way to deepen and expand the imaginative vocabulary of their artistic practice. Despite living on opposite sides of the world they have also found inspiration in some of the same sources and deployed similar images. Like other women writers and artists striving to create both more personal and more socially aware visions of their worlds, both have produced works that reclaim or “re-write” patriarchal and nationalist myth.

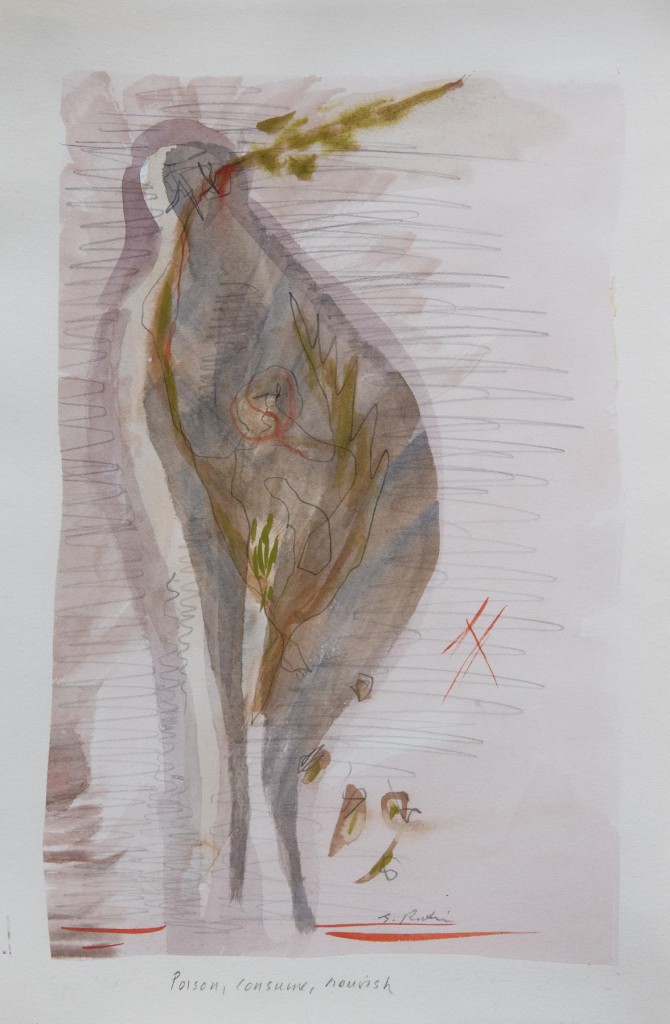

In this woodcut with water color, Rubin revisits the tale of Persephone’s banishment to the underworld. After Hades, the king of the underworld, kidnapped Persephone, her mother, the Earth goddess Demeter, pined for her and was so distraught that nothing grew on Earth. But Zeus, Persephone’s father, said that she could leave only if she had refrained from all food while in the underworld. Alas, Persephone had sucked on a few pomegranate seeds and so had to live for part of every year with Hades, thus causing winter. Rubin was particularly struck by the way that Zeus punished Persephone for eating the pomegranate seeds, a simple act of survival. “Poison, Consume, Nourish,” is also about eating and resistance as a woman’s story. (see below)

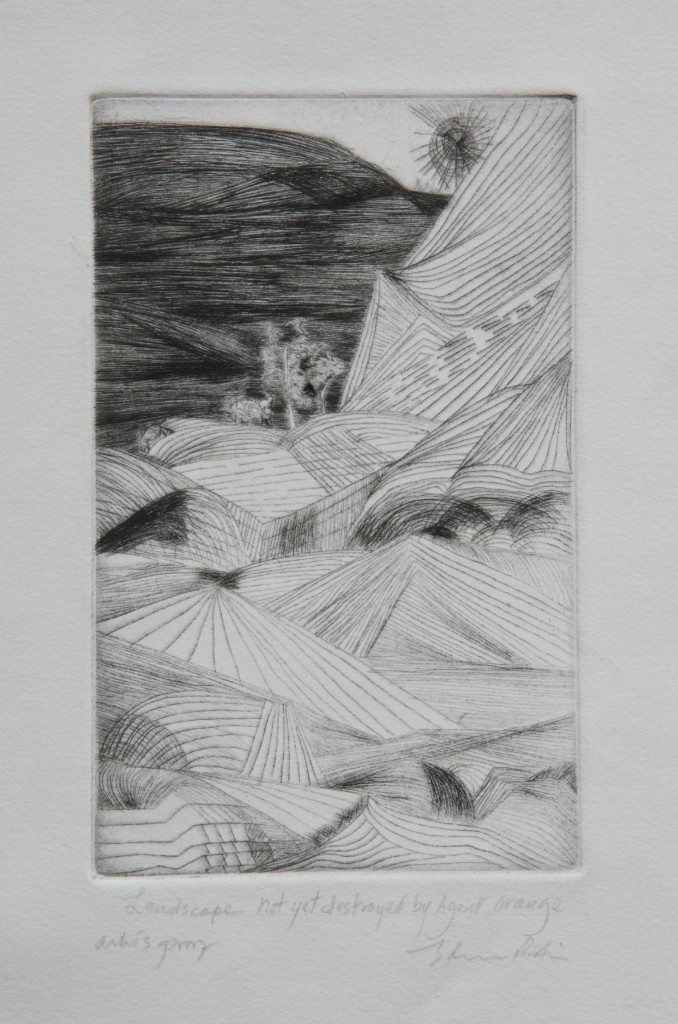

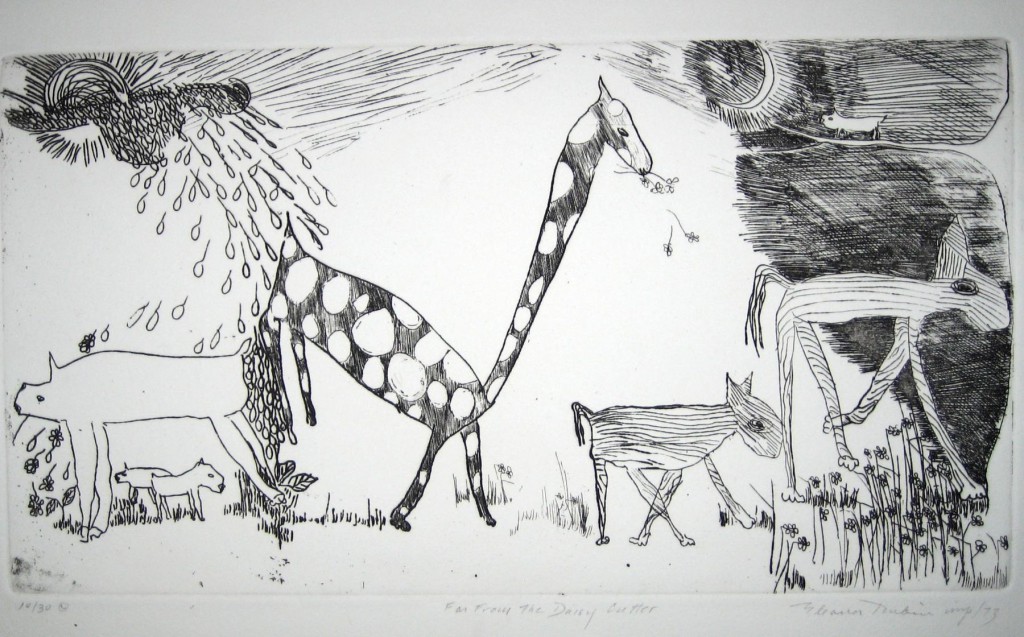

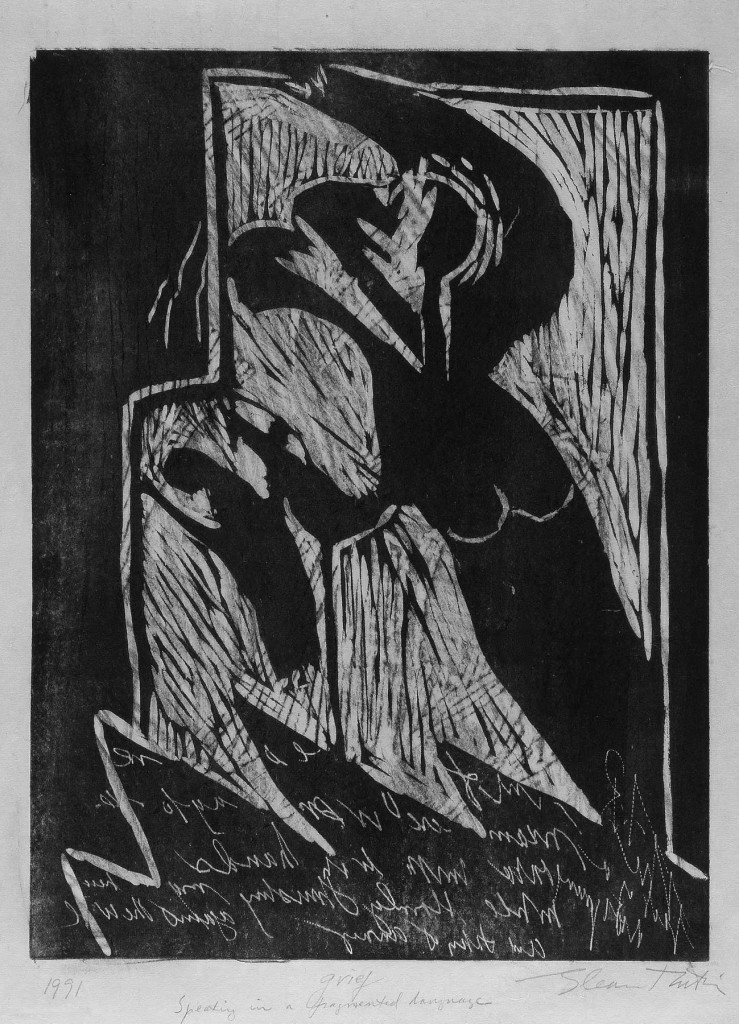

Meanwhile, Rubin, like Tomiyama, has invented her own mythic vocabulary, in which various images represent elemental forces. Her prints and drawings are replete with birds, fish, and hybrid bird/women creatures. These creatures stand for vulnerable beings who cannot speak for themselves in a world dominated by war and enforced silences. In Rubin’s work, menace is often hidden between the lines or just outside the frame as in “Far From the Daisy Cutter,” referring to a bomb used by U.S. forces in Vietnam. Another peaceful image, “Landscape Not Yet Destroyed by Agent Orange,” evokes the powerful defoliant widely used in Vietnam, which is now recognized as the cause of birth defects and several degenerative diseases. Both artists have also returned to their personal memories of their childhood—filtered through their later perspectives as adult women—as inspiration for recent work.

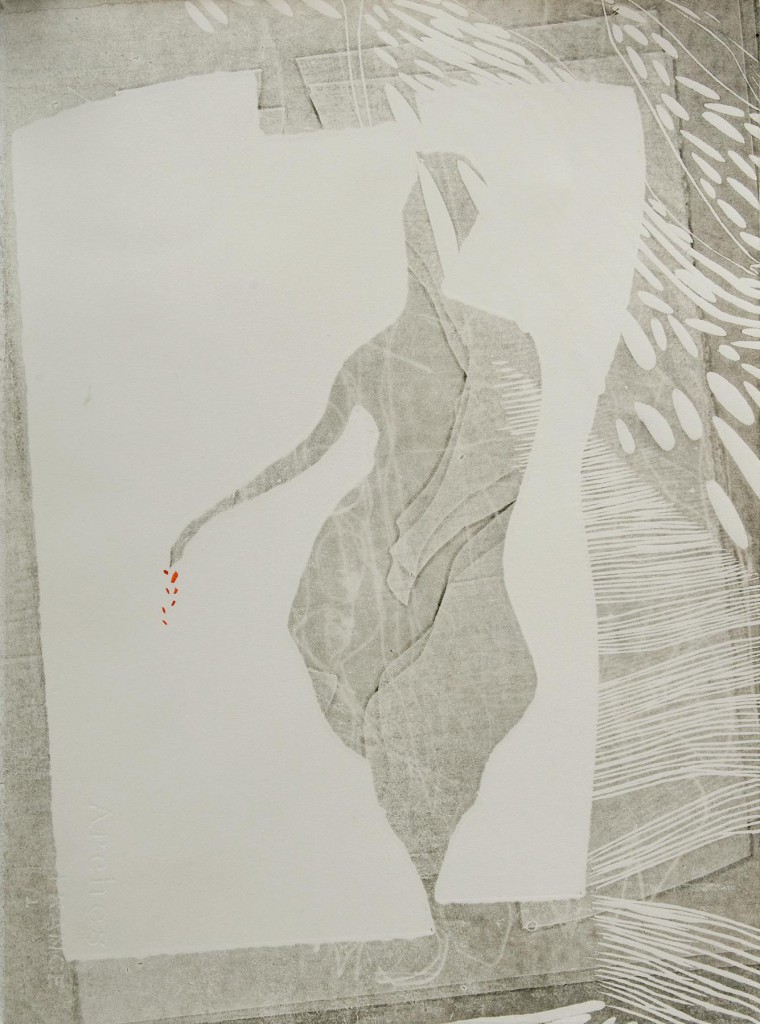

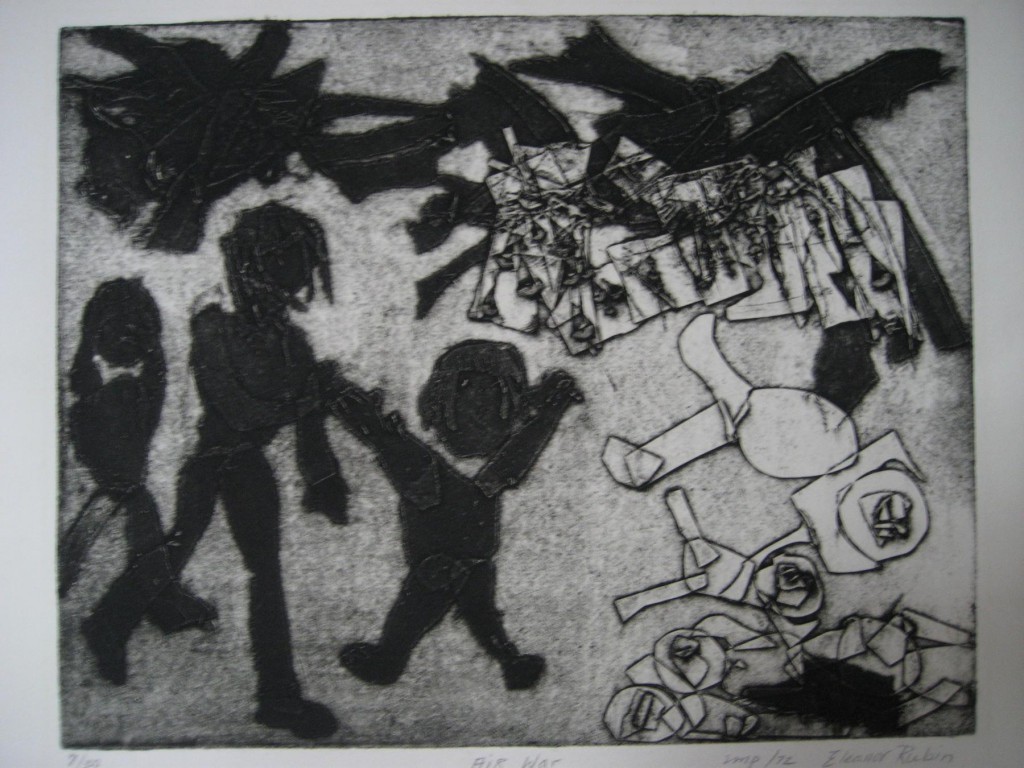

Rubin experimented with non-traditional materials, such as a complex layered printing plate that caught ink in crevices in order to make very dark images. She used that to create her response to a famous and shocking Vietnam War-era photograph after an American napalm attack that burned the skin and clothing of children running down a road. This image is a collograph, using found materials that are arranged in a collage, affixed to a board, and inked for printing on a press.

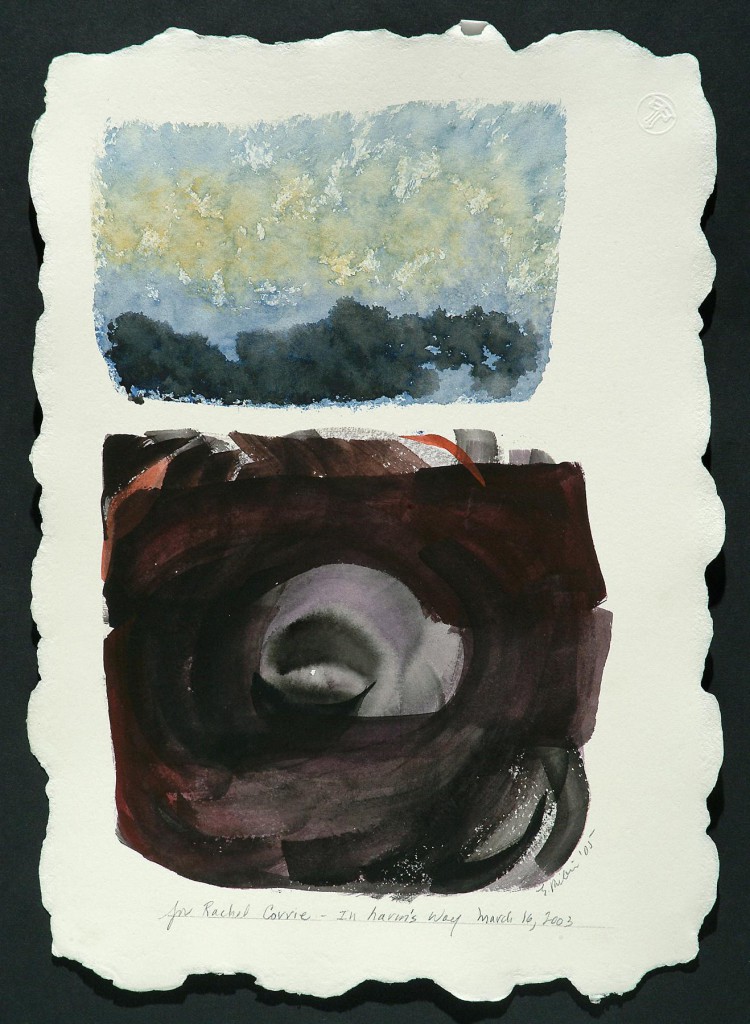

In another series, Rubin comments on brave individuals—all female—who have crossed national and cultural borders to literally stand in harm’s way to protect others from injustice. One was Rachel Corrie, a young American who was killed in 2003 by an Israeli soldier operating a bulldozer, when she stood in front of a Palestinian home in the Gaza Strip. Like Tomiyama in her series on Korean prisoners, Rubin is concerned about official brutal acts against individuals who are non-violently protesting unjust policies and practices.

Rubin’s recent work has been influenced by Japanese printmaking practices as well as by western artists such as Käthe Kollwitz. Yet, strikingly, she did not face the same challenges when engaging in this cultural borrowing as did Tomiyama. Finding an “authentic” voice is not as complicated an issue as it is for non-Western artists. Nor does borrowing from Japan raise the same issues for her as are evoked when Tomiyama borrows from the European tradition. Indeed, Japan operates in Rubin’s consciousness as a marker of imaginative and artistic possibility both symbolically and technically. It represents connections to faraway people without the need for verbal communication. This theme is especially pronounced in a children’s book Rubin created about Oe Hikari, the autistic son of Nobel laureate Oe Kenzaburo. Hikari learned to communicate with other human beings through, first, birdsong and then other forms of music. Japan often serves for Americans as a highly abstract symbol for rethinking American society and its relationships with the rest of the world. While Japanese have conducted similar thought-experiments about America in the last two centuries, the different places their nations occupy in the narrative of global history means that they cannot have identical meaning. It is striking that “Japan” offers such a sense of imaginative openness and human communication for Rubin when “Europe” has had the opposite effect on Tomiyama.

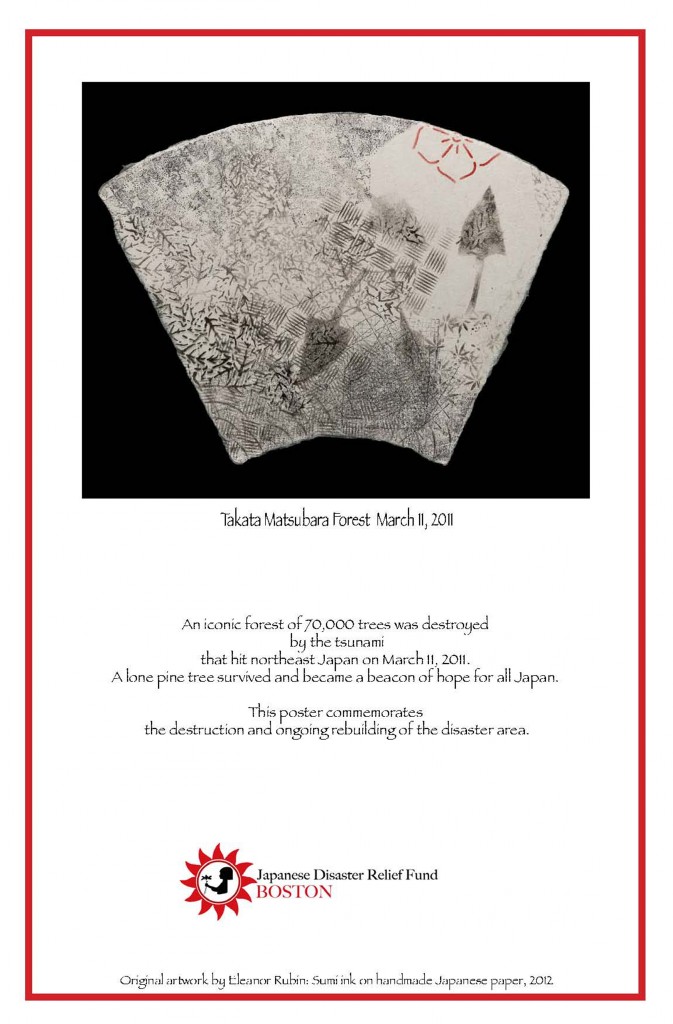

The two artists have continued to think in similar ways in other respects, however. Rubin, like Tomiyama, directly responded to the earthquake-tsunami-nuclear disaster of March 11, 2011 with new images. Her print of a seaside forest that was washed away by the tsunami—except for a single black pine—was chosen as a poster for the Japanese Disaster Relief Fund. More optimistic than Tomiyama, Rubin emphasized the “beacon of hope” represented by the lone surviving tree. Alas that tree later died, poisoned by the salt deposited by the gargantuan wave. Nonetheless, the citizens of Rikuzentakata, the town nearest the forest site, are rebuilding both their city—at a higher elevation—and the forest, with seedlings from the original trees. Thinking along much the same lines as Rubin, they have also decided to keep the lone pine—now essentially a sculpture of a pine tree created from the deadwood—as a symbol of their collective experience.

Rubin has maintained the theme of global environmental connectedness—and the way that war makes sustaining both the natural and human communities difficult—in her most recent work as well. One way she has done so is through the image of a leaf from a gingko tree, in full knowledge that many gingkos grow in Japan, including some ancient trees that survived the atomic bombing in Hiroshima in 1945. Gingkos are an especially long-lived species and have the reputation in Japan for protecting nearby buildings from fire, although not atomic blasts. Rubin has turned her thoughts to the importance of shelter—homes, roofs, trees, families, our blue planet.

As Rubin explains: “My leaf is from a local tree. I used the leaf as a stencil, and the support, a roof-slate fragment from our house, suggests strength, protection and vulnerability. These gray slates are not considered valuable by builders and the workmen tossed them to the ground as they ripped them off our roof, which had to be replaced after sheltering this house for 90+ years. The slate fragments I collected from the ground suggested images and ‘Gingko Blue’ is one of those images.” Her art is reparative: it is designed to weave a protective narrative around her own house, but also around people whose lives have been upended by such disruptions as tsunamis and wars. And she continues to remind us that it is never too late to take responsibility to repair the damage we have done to others, by evoking the six trees in Hiroshima.

See “Talking Across the World: A Discussion Between Tomiyama Taeko and Eleanor Rubin,” introduced by Rebecca Jennison, in Laura Hein and Rebecca Jennison, eds., Imagination Without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility, Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan.

The Digital version is fully and freely accessible on the University of Michigan Press website.