When Tomiyama completed Hiruko and the Puppeteers—A Tale of Sea Wanderers, she assumed that it would be the last of her major works. Then on March 11, 2011, the Tohoku region of Japan suffered a massive earthquake and tsunami. An estimated 18,456 people died or disappeared without a trace and whole communities were washed away. The horror of that event was compounded by a man-made disaster: the uncontrolled melt-down of three side-by-side nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Dai-ichi site owned by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO). The tsunami flooded the reactors along with three others that had been shut down for maintenance. Up until that point Japan had enjoyed a reputation as an effective modern society that delivered what people needed in a timely and efficient manner. Although the two decades of poor economic performance leading up to 2011 had dented that image both at home and abroad, few people were prepared for either the callousness or the sheer ineptness with which TEPCO and the national government responded to the triple disaster. It soon became clear that the electric power company had inadequately prepared for a tsunami, bungled its response, and then tried to cover up its problems. The national government has ever since seemed to care more about protecting TEPCO and ignoring the effects of radiation than the health and welfare of Tohoku residents. Nor is the danger resolved: as of this writing, TEPCO is still removing radioactive debris in order to begin retrieving the fuel rods in the reactors and still generates hundreds of cubic meters of radioactive water a day keeping the rods cool. The water is stored on site for partial decontamination. Those ever-growing millions of gallons of water will end up in the Pacific Ocean, since the plans for containing it on land are obviously inadequate.

As Tomiyama herself put it, “On March 11, 2011 … the world was shocked and all eyes were on Japan. As I live in Tokyo, I held my breath and watched the TV news. The force of the magnitude 9 earthquake was unimaginably fierce. The earth shook, sea currents reversed and swallowed land. The tsunami turned 600 kilometers of coastline into ruins. Was this the end of modern civilization? This was the theme of Revelation from the Sea, a work that took 3 years to complete!”

In other words, Tomiyama’s signature themes gained new and tragic contemporary relevance. Once again Japan’s citizens felt betrayed by the leaders they had chosen. Moreover, the disaster occurred because they had far too eagerly responded to self-flattering rhetoric celebrating Japanese technological sophistication and national community. In retrospect they should have paid better attention to earlier nuclear disasters that had also revealed callous incompetence although not on such a mammoth scale. Their complacency and its consequences is the central theme of Tomiyama’s 2014 work, Revelation from the Sea, completed when the artist was 92 years old.

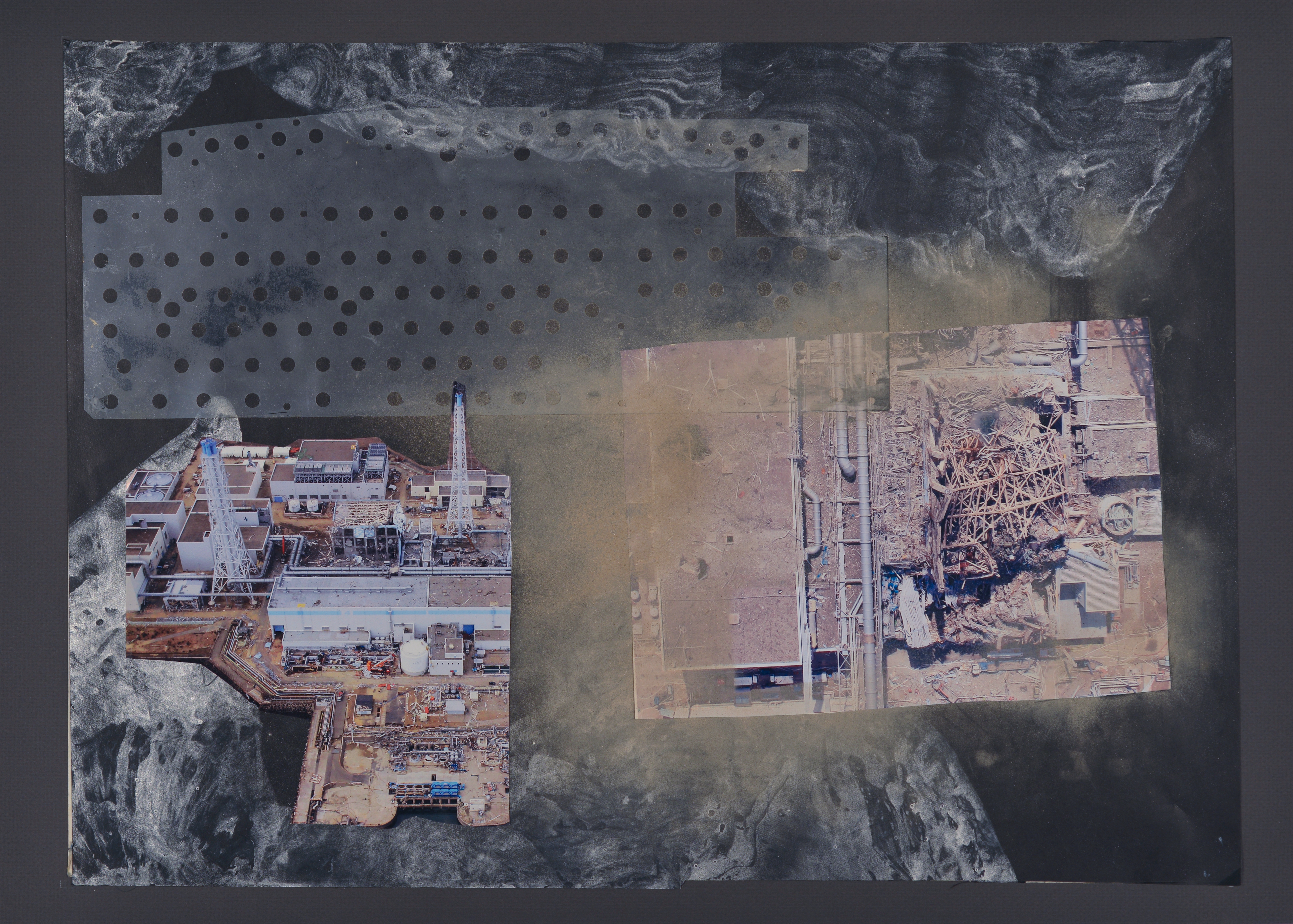

As with her earlier series, Tomiyama not only mobilizes her own images and texts but also summons a deep reservoir of intertextual references drawn from Japanese folk traditions, major Asian religions, global icons of modernity, and the news headlines. The central core of the series consists of four large oil paintings, including “Japan: Nuclear Power Plant,” which portrays one of the crippled reactors at Fukushima with its roof blown off by a nuclear-fuelled explosion. Although Reactor #4 was shut down when the tsunami struck, 1,770 intensely radioactive fuel rods had just been loaded into a top-floor cooling pool to decay, in a General Electric Company reactor design that now seems ill-advised, although it is common throughout the world.

Like all her work since Memories of the Sea, Tomiyama has adopted the metaphor of traffic between the world of humans and of gods, although drawing on new deities each time. Two of the four paintings in Revelation from the Sea present the gods of wind and thunder, Fūjin and Raijin. This pair of supernatural beings is linked to a variety of transnational Asian beliefs as well as to Shintō mythology. Most recently, on-line video gamers have incorporated these gods into their creative practice, giving Fūjin and Raijin far broader global recognition in the twenty first century. In Tomiyama’s rendering, Fūjin presides over a pretty pink cloud of cherry blossoms laced with Caesium-137 while Raijin hurls his thunderbolts and rattles his drums across a stormier sky.

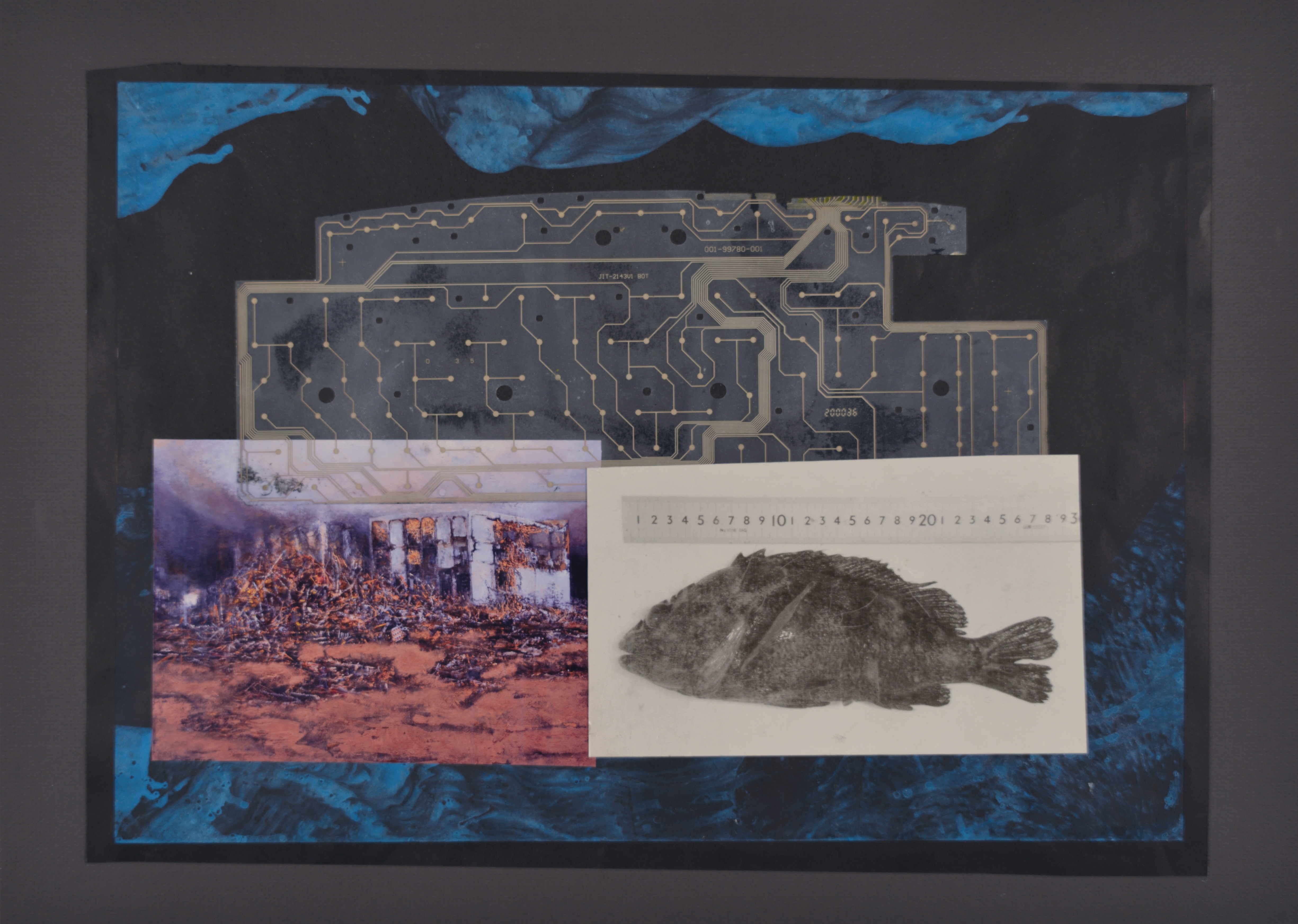

Revelation from the Sea also includes fourteen collages, primarily in grey, black, and brown as well as a new collaborative DVD created with Takahashi Yūji, also named Revelation from the Sea. The collages develop the theme of environmental destruction, a concern that she touched on in earlier work but is at the center of this series. The taxonomic presentation of dead fish and moths make it clear that her target is the arrogance with which people today deploy all modern technology rather than just its manifestation in nuclear power plants. Tomiyama has also disassembled a computer motherboard and the guts of several cell phones, now pasted into the collages and paintings, to drive this point home.

죽은 나비에게: 후쿠시마 4 나비의 시 | To The Dead Butterfly: Fukushima 4 | 死せる蝶に: 福島 4 (2013)

죽은 나비에게: 후쿠시마 4 나비의 시 | To The Dead Butterfly: Fukushima 4 | 死せる蝶に: 福島 4 (2013)

By far the strongest new statement, however, is Tomiyama’s direct meditation on the inevitability of death and perhaps even “the end of modern civilization.” She presents this topic in two ways, one that connects her work to the core figures of the modern European artistic tradition and another that anchors it firmly within the single most philosophical and cosmopolitan Asian tradition, Buddhism.

Tomiyama says that “when I stand at a difficult crossroad, I recall this poem by Goethe,” which she read in Japanese. Her attention lingers on the final stanza, which tells of a butterfly that cannot resist flying straight into a deadly flame.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s poem, originally written in German, has been translated into English in several ways. Here is the last stanza in two of these translations, by Robert Bly and A.S. Kline.

Distance does not make you falter. / Now, arriving in magic, flying, / and finally, insane for the light, / you are the butterfly and you are gone. / And so long as you haven’t experienced this: to die and so to grow, / you are only a troubled guest on the dark earth.

No distances can weigh you down, / Enchanted you come flying, / And greedy for the light, at last, / A moth, you burn in dying. / And as long as you lack this / True word: Die and Become! / You’ll be but a dismal guest, / In Earth’s darkened room.

Tomiyama’s most imposing painting in this series depicts the Four Heavenly Kings, who protect Buddhism from north, south, east, and west, and also keep track of human behavior. Like Fūjin and Raijin, they appear in other religions as well, notably Hinduism, and also are associated with wind and rain. This is the first time that Tomiyama has emphasized Buddhism, the Asian religion that most fully explains death and prepares us for the end of life. The gods in her earlier work were stand-ins for humans, but these Buddhist deities are judging and sadly scolding us. Moreover, Tomiyama’s criticism here is directed, not at war, or imperialism, or capitalism, or sexism, as in her previous work, but more precisely at everything that causes suffering, aligning her attention with the central message of Buddhism. She reminds her viewers that we are all troubled guests on this dark earth.