Dedicated to the Memory of the Korean Comfort Women

Like many women of her generation around the world, when Tomiyama first encountered feminism, it seemed to give words to feelings that she had never been able to articulate and—for the first time—to explain her own life in ways that made sense. It also changed the way she worked. In the late 1980s, Tomiyama returned to oil painting and to greater use of color, choices that she attributes to new perceptions built on feminist insights.

Feminism also provided a new grammar for the “Asian visual language” that Tomiyama was developing in her art. She had already gone back to antiquity for the images that take center stage in Heaven and Earth. In the 1980s she focused on ancient myths and religious symbols (both European and Asian), prompted by contemporary feminist scholars who argued that these were sometimes lingering traces of non-patriarchial societies in the distant past. This turned out to be a very productive development for her art.

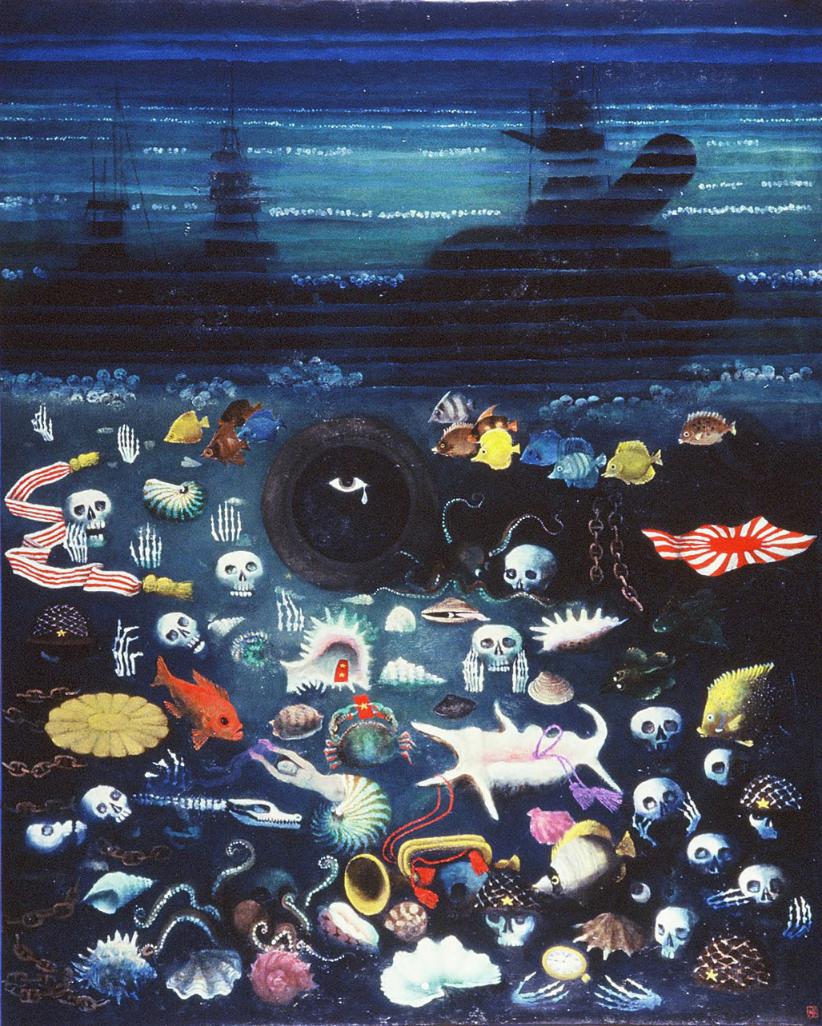

One central aspect of this new visual language was the metaphor of traffic between the world of humans and that of spirits. These new metaphors allowed her to comment on relations of power within human society, her true subject. This theme is at the center of her 1984-1985 collection, Memories of the Sea. In these two large canvasses plus several collages, Tomiyama brought feminism together with the rich symbolic resources of Asian folk religion in order to portray the cruelty of imperialism and war, as well as the hypocrisy of postwar Japanese society. “The Festival of Galungan,” depicted in a deep red canvas, is a Hindu religious event, celebrated on the Indonesian island of Bali, which represents the triumph of good over evil. At that time, the ancestral spirits return to earth to visit their families, making it the moment in the year when such travel is easiest.

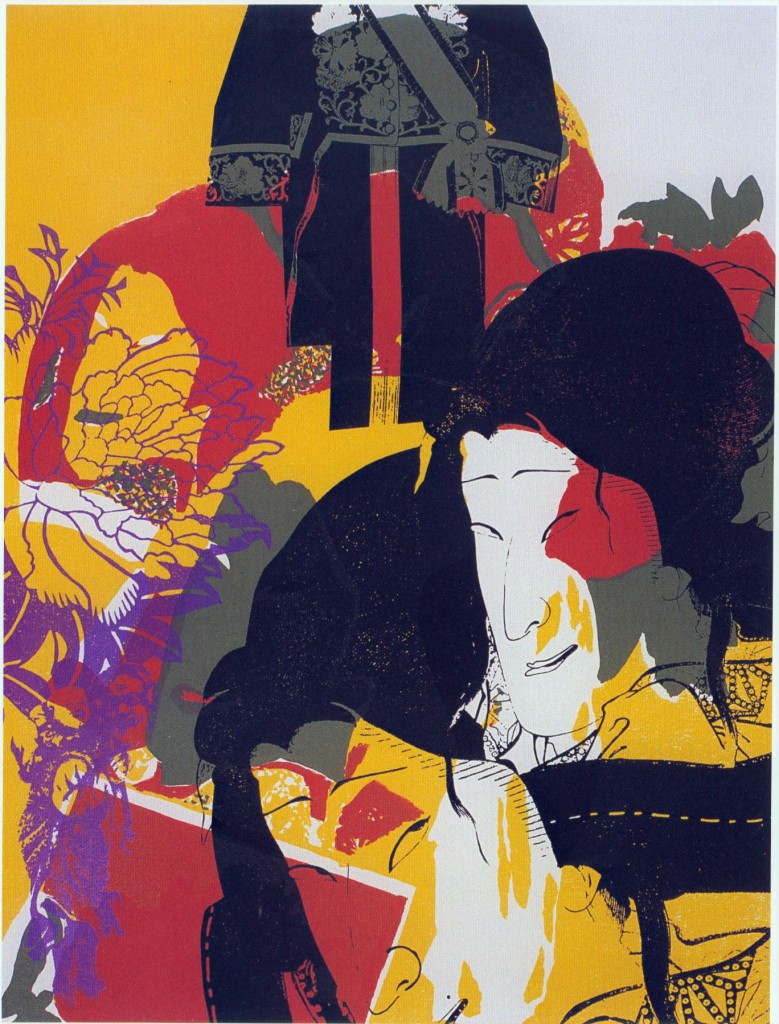

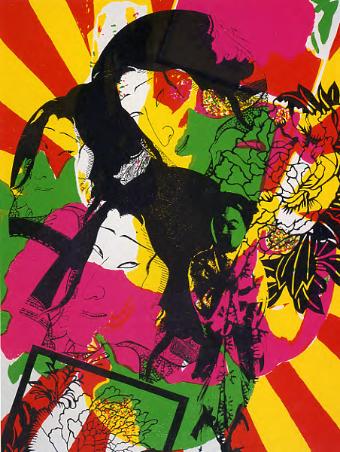

The most important of Tomiyama’s supernatural images is the shaman, an often female figure in much North Asian folklore, who commands powers that are neither good nor evil. The shaman appears, for example, in Kurosawa Akira’s 1950 film, Rashomon and plays a central role in Korean and Siberian culture. Tomiyama first introduced the shaman into her work in the 1980s, beginning with the 1984 lithograph series, Coerced and Forlorn, on Korean miners forced to work in presurrender Japan.

Memories of the Sea is also the first of several sets of artworks that Tomiyama linked together in a specific sequence to narrate a quest or journey. In this series, a young Korean woman enlists the shaman’s help to search for her sister who was taken away by the Japanese army and whose bones now lie at the bottom of the sea. The shaman who guided her is depicted in the collage on the About page of this website.

Tomiyama decided to focus on the Korean “military comfort women” who were conscripted to provide sex to Japanese soldiers during World War II. While many Japanese knew about this practice, the explosive combination of war, colonial oppression, and state-sanctioned rape on a massive scale meant that few were willing to talk about it. Most of the women had died during the war and those who survived were dishonored in their own societies and in Japan. The first such individual to speak out publicly, Kim Hak-sun, did not do so until 1991, five years after Tomiyama painted this series.

The move toward mythic figures allowed Tomiyama to focus far more directly on visual representation of suffering victims than she had in the past. Memories of the Sea emphasizes the messy, unresolved, painful, shameful, and ambivalent problems left behind in the wake of war, directing attention to broken bodies and bereft families, a subject she had first broached in her lithographs on Korean miners. Rather than mobilizing her viewers’ outrage, Tomiyama aimed at their capacity to empathize. While her primary intended audience is Japanese, she has also shown this work in Europe, North America, and South Korea.

In Tomiyama’s version of the Festival of Galungan, the goddess Rangda presides. While Rangda is usually portrayed as the evil spirit to be vanquished, Tomiyama suggests that perhaps she has good reason to be angry. In this feminist reading, Tomiyama reimagines the scene precariously poised between horror and celebration, as we realize that the naked young women are the sacrificial gifts rather than the worshippers.

Tomiyama also returned to her earlier collaborator, musician and composer TAKAHASHI Yūji, to create a slideshow (now a DVD) of images of sections of the paintings and collages in this series. This slideshow/DVD operates independently as a different original artwork. Takahashi Yūji, one of Japan’s best-known contemporary composers, wrote music—for both traditional instruments and for computer—that the two artists coordinated with the slides into a performance art piece. Tomiyama sees their collaborative work as similar to the practice of medieval monks who used music and picture scrolls (emaki) to spread their doctrine of faith in the Buddha. At the same time both artists are exploring very contemporary media idioms.

Tomiyama’s next works took up the subject of Asian women who were then being trafficked to Japan, a staggeringly profitable business at the time, and still huge today. Both the slide show A Thai Girl Who Never Returned Home (1991) and the paintings that comprise Let’s Go to Japan (1991) focused on the ongoing plight of Asian women in Japan who are forced into prostitution through imprisonment and debt peonage.

In 1994 Tomiyama created a series of serigraphs modeled on traditional woodblock prints that depict young Japanese women sent to the continent in the late nineteenth century to earn foreign exchange for the nation in the brothels of Southeast Asia. By the start of the twentieth century, half the Japanese people traveling to Harbin were “karayuki-san.” The health and happiness of these young girls were sacrificed by their families so that their brothers could continue in school and also by the Japanese state so that the nation could modernize. Visually, the serigraphs refer to the long tradition of depicting women of the Japanese demi-monde in prints as well as to the even longer tradition of selling daughters into prostitution.

See Rebecca Copeland, “Art Beyond Language: Japanese Women Artists and The Feminist Imagination” and Laura Hein “Post-Colonial Conscience: Making Moral Sense of Japan’s Modern World,” in Laura Hein and Rebecca Jennison, eds., Imagination Without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility, Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan, 2010.

The Digital version is fully and freely accessible on the University of Michigan Press website.