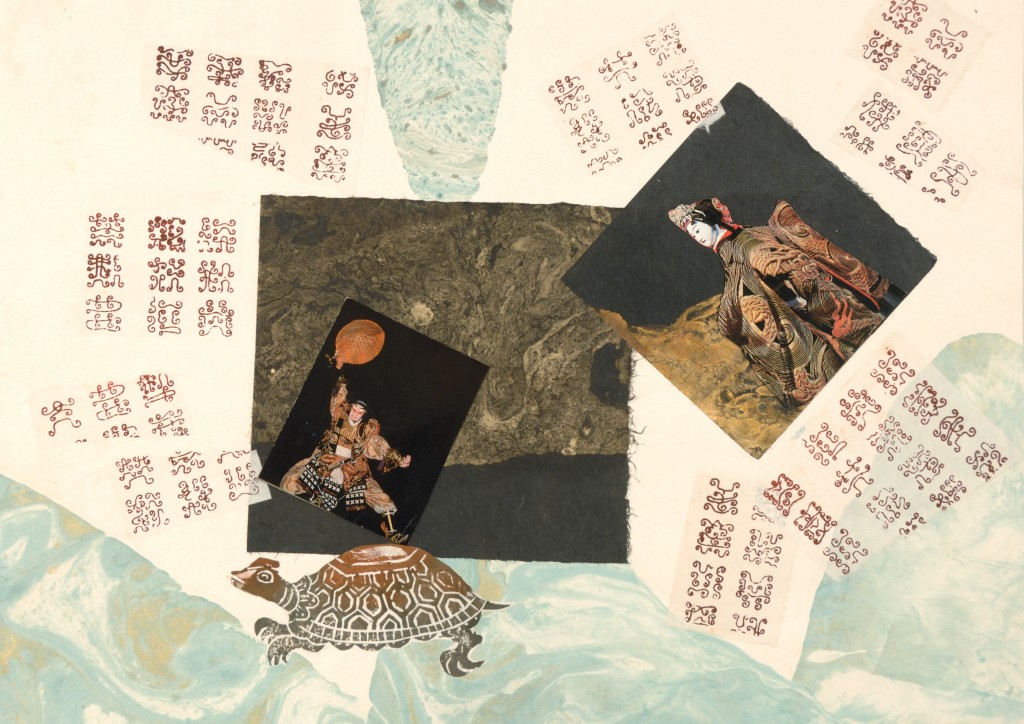

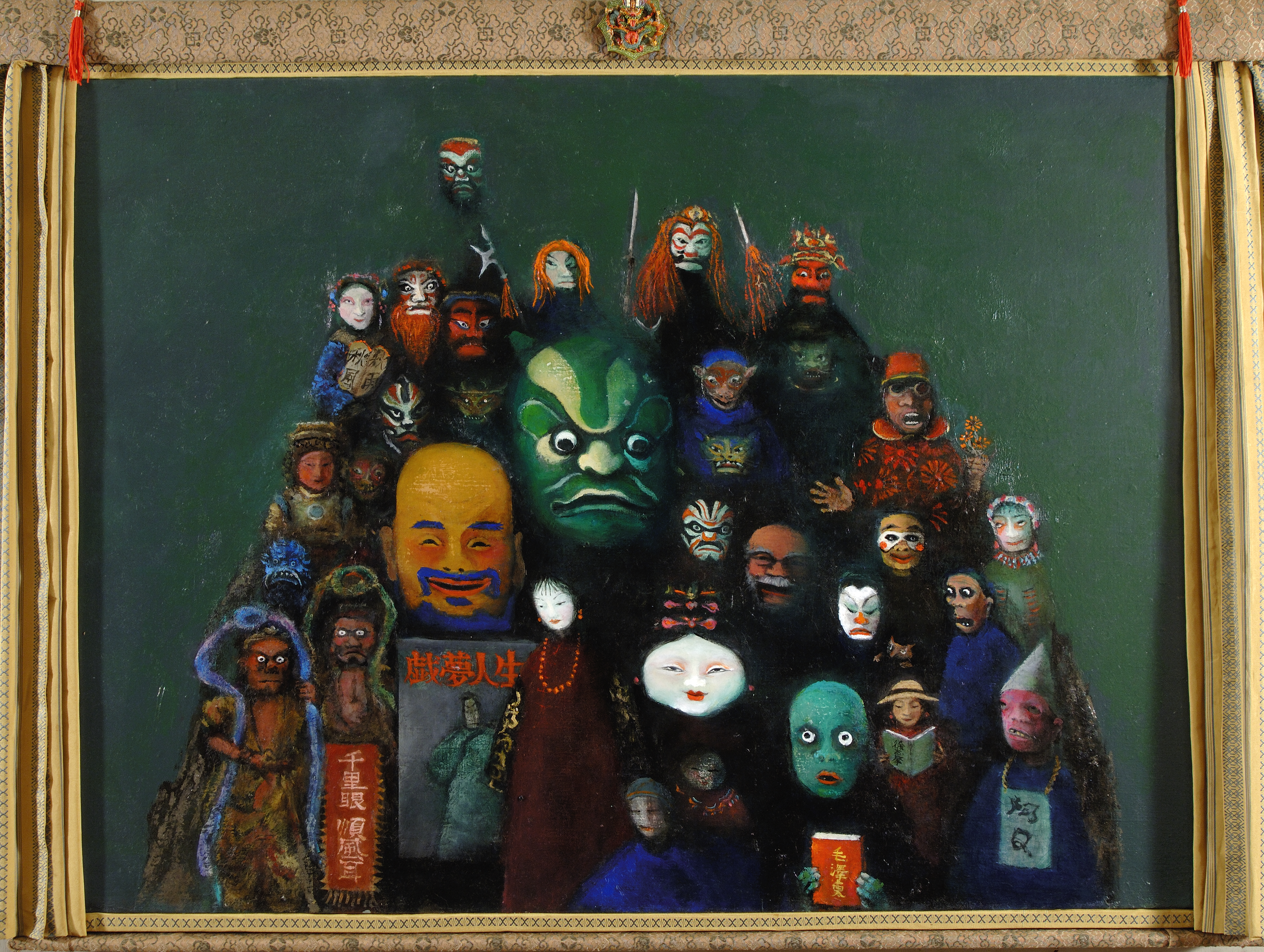

Tomiyama’s 2007-2009 series is her largest and most ambitious since Harbin. It sustains her longstanding focus on transnational history, warfare, and Japan’s relationship with Asia. The paintings and collages depict the journey of a group of Asian masks, dolls, and puppets from Central Asia via rivers to the Chinese coast; then on to Awaji, an island in Japan that is the childhood home of Tomiyama’s parents and has a distinguished history of political liberalism and of traditional puppetry; then to the waters off Southeast Asia and New Guinea. Japan is a stop along the way but neither the cultural originator nor the culmination of the journey.

The travelers include Malaysian and Indonesian puppets, Polynesian masks, and Japanese folk figures, such as Otafuku. Tomiyama calls these puppets troubadours (tabi-geinin) to evoke the medieval wandering artists who carried culture and religion with them, mingling and transmitting ideas without regard to national borders.

Predominantly a verdant green color, these paintings evoke an undersea world in which puppets and folk gods, cast off by human society, represent the culture and ecology that have been left behind as the drylanders rush to enrich themselves, heedless of the physical and moral destruction they are causing.

The culprits here are imperialism and industrialization. While Japan and the Western countries were the worst offenders, Tomiyama is commenting on the twentieth century as a whole, reminding us of what has been lost in her lifetime. She begins her story with an “original sin:” the founding deities of Japan rejected their firstborn child, who did not have a human form, by casting him out to sea. The Hiruko, or boneless child, became the fisherman’s protector, Ebisu. Ebisu in this narrative is linked to the Chinese folk goddess Mazu, who also watches over those who travel by sea.

In the era of imperialism which soon followed, Asians prayed to Mazu and Ebisu not for spiritual inspiration but only for material prosperity. In her story, the puppets were decimated by war but also were consigned to their watery graves by human disinterest, as people turned to the mass amusements of cinema and animated cartoons. Yet the present moment is not without hope, in Tomiyama’s tale. The puppets somehow, mysteriously, are keeping creativity and culture alive, should humans wish to reclaim these attributes.

The last painting of this series, evoking the twin towers of the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, is a warning that time is short. It also brought Tomiyama back to the theme of joint Japanese and Korean subservience to American military policy in Asia. Tomiyama also wished to evoke an oil-field fire, destroying the atmosphere as it provides the pretext for yet another war. She sees the present as another moment of massive—and all too willing—self-delusion. Yet the bird skeletons picking their way through a graveyard of computer keyboards are oddly cheerful, giving a light-hearted touch to her sober message.

See “Talking Across the World: A Discussion Between Tomiyama Taeko and Eleanor Rubin,” particularly the introduction by Rebecca Jennison, and Hagiwara Hiroko, “Working On and Off the Margins” in Laura Hein and Rebecca Jennison, eds., Imagination Without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility, Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan, 2010.

The Digital version is fully and freely accessible on the University of Michigan Press website.