In the 1960s, Tomiyama travelled through Asia and Latin America in search of new artistic ideas, an experience that helped her develop her own “Asian visual language” that no longer felt either imitative or nationalistic but acknowledged Japan’s place in the Asian cultural and artistic tradition.

This chapter of Tomiyama’s life actually began in 1961 with a year-long trip to Latin America, including a stopover in South Africa. She chose Latin America because some of the unemployed coal miners who were blacklisted for union activities in Japan had emigrated there, and she planned to write about their experiences in their new home. This and subsequent lengthy journeys to the Asian mainland changed the way she saw both the global artistic tradition and her own art. These “tours of former colonies” brought home to Tomiyama the ways that European artistic movements such as Cubism had appropriated African art in a process that had robbed Africans of subjectivity and recognized as art only the work of white people. She was further excited to see the ways that Latin American art forms, including African-inspired music, both drew on and differed from European ones.

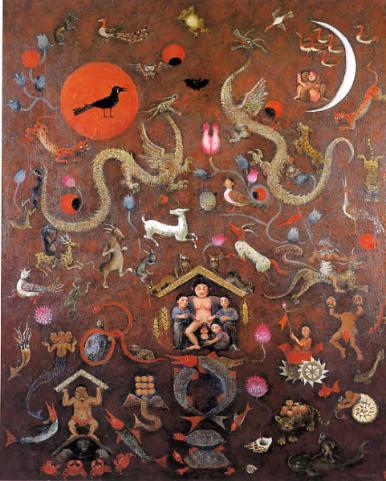

Tomiyama began developing her “Asian visual language” in “Those Who Fly in the Sky” which she painted the same year that she worked on Memories of the Sea. Not only does it mark her return to oil painting and the use of color after a twenty-year hiatus, this canvas also combines a wide variety of artistic inspirations in a single piece in a highly imaginative and personal way. “Those Who Fly in the Sky” is also an explicitly feminist artwork, marking the moment in her life when she encountered that powerful new imaginative framework.

Tomiyama modeled this painting on an important silk funerary banner discovered in the early 1970s in an ancient Chinese tomb at Mawangdui. Tomiyama retains the color palette and much of the imagery of the original banner, which shows the travel of souls from earthly life to the realm of the immortals. The central image in the banner was of King Fu Xi going to heaven on a chariot pulled by dragons. He represents the founder of the Chinese race and the first ruler of China, as well as showing the path to immortality. When Tomiyama looked at the banner, she thought, “Why is the king in the chariot? A woman giving birth is far more important,” and she replaced the king with an image of a standing woman assisted by attendants, a traditional birthing style in Japan.

Tomiyama retained the bird in the moon and the dragons, which have symbolic resonances both within Japan and in other parts of Asia. But she also layered on new meanings, cramming the painting with private symbols. The dragon represents the “education mama” urging her child to claw his way up the status ladder in Japan today, while the radical Latin American educator Paolo Friere is in the lower left corner, as Tomiyama mocks the cult of meritocracy through educational achievement and the way it organizes social ambition in postwar Japan.

The tiger in the lower right is from the Book of Isaiah, when the lion lay down with the lamb and enemies are reconciled, although the African lion has been replaced by the Asian tiger. Meanwhile, the dancing figure with heads on his hands comes from the same ancient Chinese imagery as the funerary banner, while other segments represent modern forced laborers. Animals, humans, and gods all pursue their own activities while the central figure brings a new person into the world.

검은 강 V (말 흑백) | Black River V (horse) | 黒い河の馬 V (1994)

검은 강 V (말 흑백) | Black River V (horse) | 黒い河の馬 V (1994)

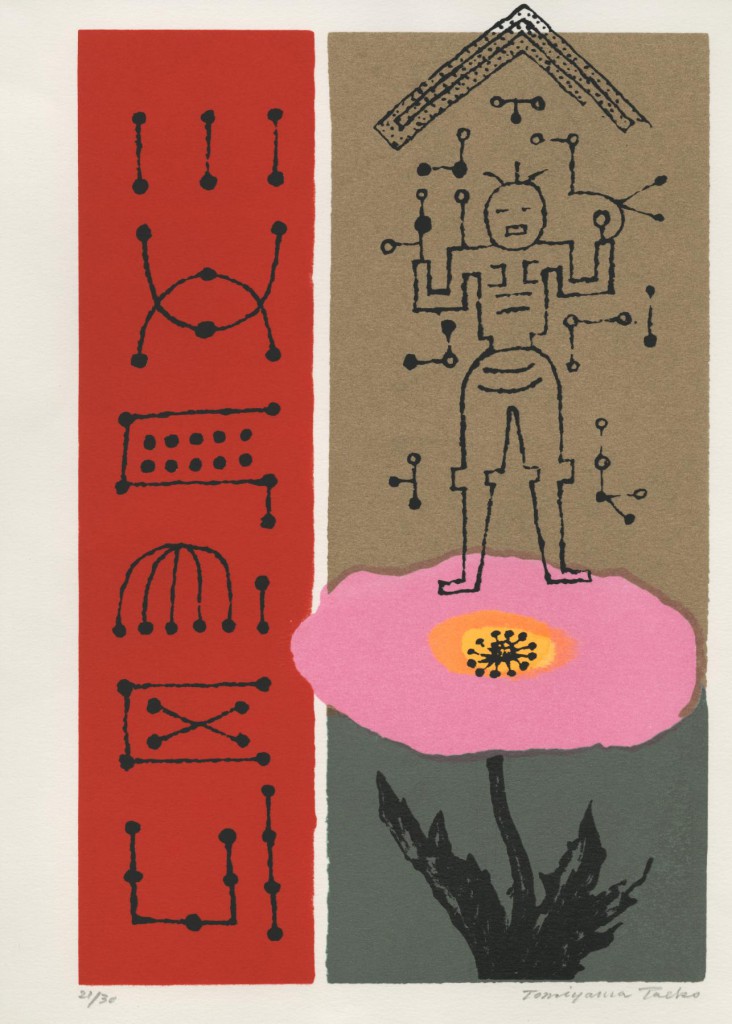

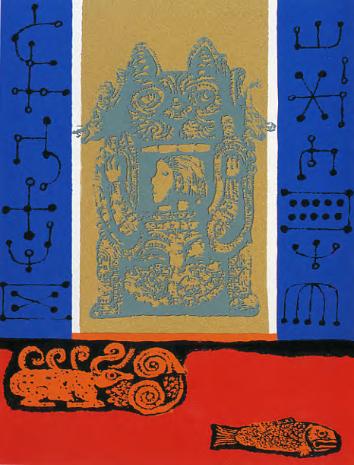

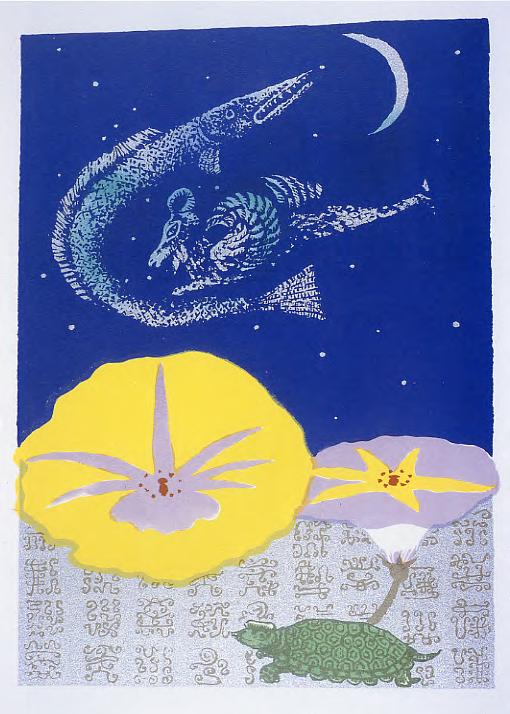

Tomiyama further developed her “Asian visual language” in a 1994 print series, Heaven and Earth in Central Asia, inspired by the Classic of Mountains and Seas (Shanhai Jing 山海經), a Chinese compilation of imaginary geographies, dating back to at least the 4th century BCE. In this series, she also borrowed images from ancient art, secret Taoist writing systems, constellations in the night sky, and the flora and fauna of Asia. The Classic of Mountains and Seas also includes mythical creatures who would appear in her later work, such as a powerful goddess with a human head but the body of a snake and the deceitful nine-tailed fox.

Tomiyama now saw all the imperial powers, including Japan, as having ruthlessly exploited their colonies and devalued indigenous forms of artistic expression in essentially identical ways. This insight did two things: first, it made clear the pointlessness of the popular 1930s Japanese fascist assumption, encouraged by the government, that the war would sweep clean the impurity of modern, Western-influenced life. Second, it also dissolved Tomiyama’s anxieties about her own relationship to the Western artistic canon. She now saw various expressive forms as having floated free of their original contexts, becoming available for whoever wished to engage and incorporate them in new ways.

See Laura Hein “Post-Colonial Conscience: Making Moral Sense of Japan’s Modern World” in Laura Hein and Rebecca Jennison, eds., Imagination Without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility, Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan, 2010.

The Digital version is fully and freely accessible on the University of Michigan Press website.