In Tomiyama’s lifetime, Japan has radically changed its boundaries, its rules of government, and its society. Defeat in World War II, followed by partition of the globe along Cold War lines, meant not only that Japan was stripped of its colonies by the stroke of a pen in September 1945 but also that afterwards Japanese postwar interaction with much of the former empire was largely structured by U.S. policies in Asia. The initial decolonization process was unusually short, and was subsumed into the general experience of defeat in war and the associated repatriation of 6.6 million people, both soldiers and civilians. For these reasons, until the 1990s, scholarly and popular attention in Japan has focused more on recollections of the war than of the empire that also collapsed in 1945. Since then, however, much work on this topic has appeared in both English and Japanese.

In the 1990s, after turning seventy, Tomiyama gave her full attention to Japan’s history of imperialism, which also meant thinking about her own experience of growing up in Japanese-controlled Manchuria. The feminist insight that “the personal is political” showed Tomiyama how to incorporate that experience into her art. This time, rather than the shaman, she chose the fox as her magical vehicle of expression. As in Europe, the East Asian fox is a trickster character, able to shape-shift and bewitch humans. It is also closely related to the Japanese imperial family, through its association with the Shinto rice spirit, among other religious connections. These foxes may appear cute at first glance but they are dangerous.

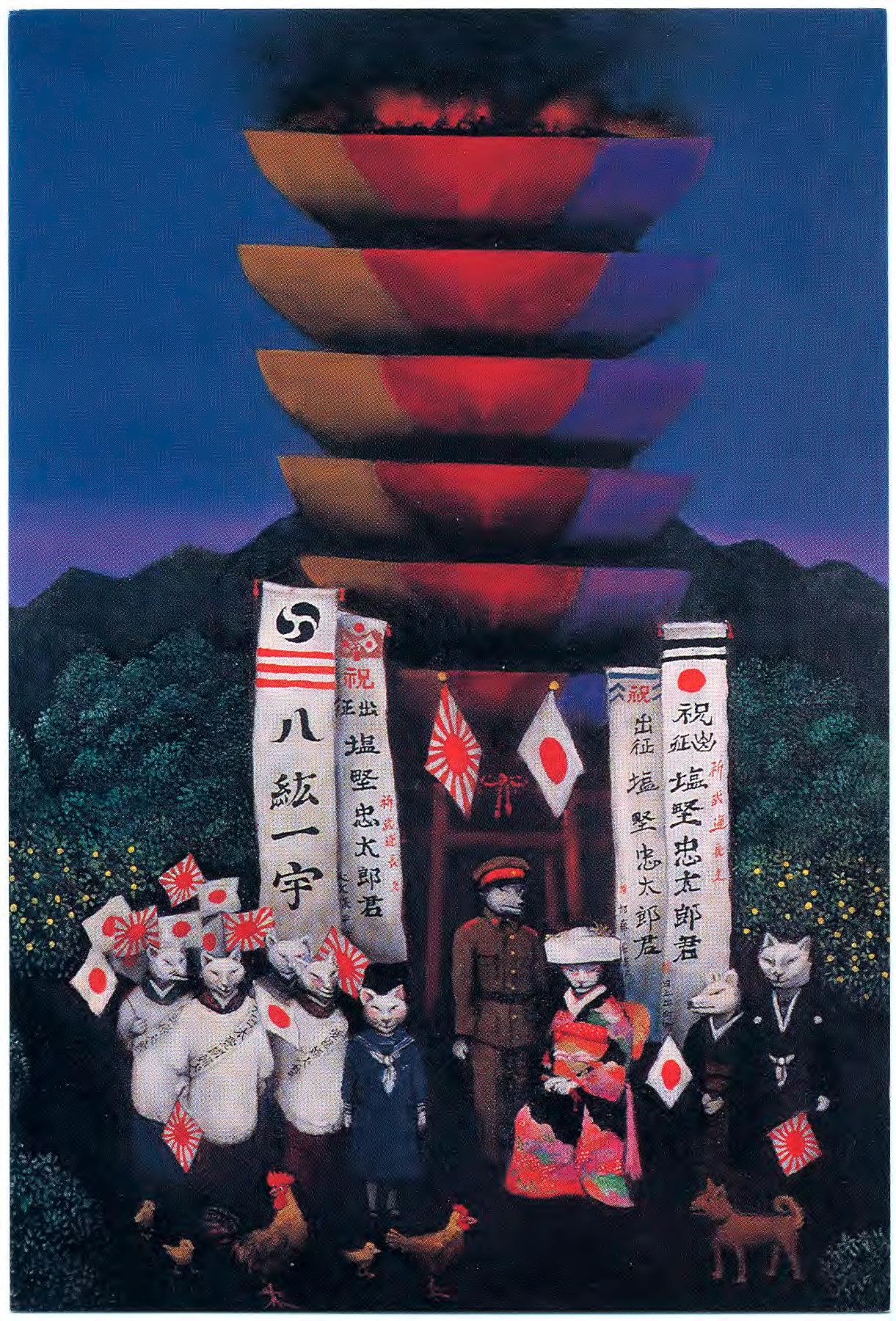

축 출정 | Sending Off a Soldier | 祝 出征 (1994)

축 출정 | Sending Off a Soldier | 祝 出征 (1994)

One oil painting depicts a fox wedding of the early 1940s in a village, playing on the fox’s long association with female sexuality. The groom is dressed in his army uniform, already prepared to leave for the battlefront. Since few soldiers expected to return from the war, many of them married hastily and hoped to sire an heir to carry on the family line before their own lives were cut short. Tomiyama uses the theme of bewitchment to capture her horror at her own younger complicity in the idea that young Japanese should hurriedly procreate and die for the nation.

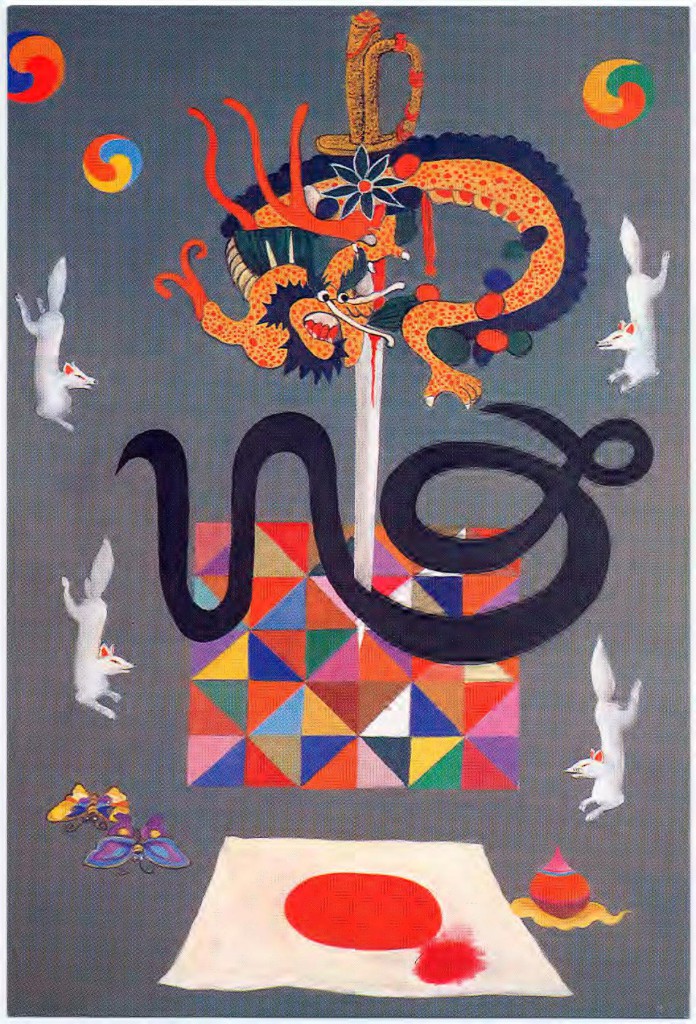

Other paintings, dominated by a deep red that symbolizes both blood and war, show the trappings of statehood for Manchukuo, Japan’s puppet state, mocking the rhetoric of racial harmony that the Japanese had used to justify their control of the region. One composition, of the Chinese character for “loyalty,” made up of a dragon, a bloody sword, and a snake, suggests that blind loyalty in the world of the fox is a one-way road to disaster, since foxes love to deceive humans into betraying their own ideals. It also highlights the way that language itself is a powerful medium of propaganda.

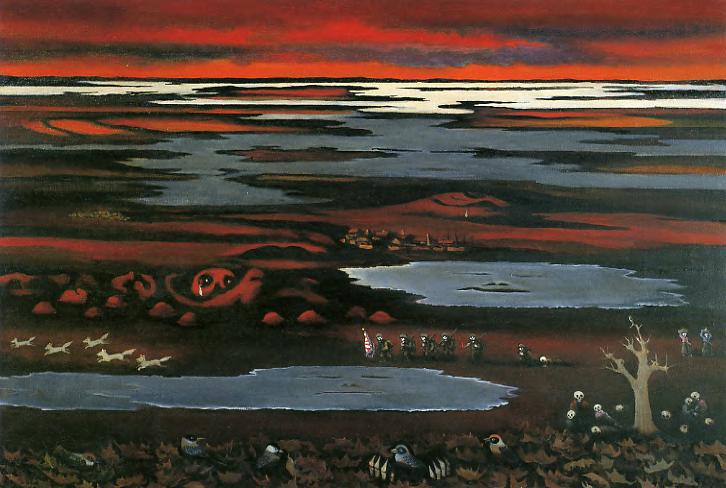

While the main focus of this series is an exploration of the ways that Japanese allowed themselves to be deceived into dying and forcing each other to die for an ignoble cause, the last painting, “Manchukuo at Sunset,” shows a blighted landscape destroyed by Unit 731, the bio-warfare research laboratory based in Harbin that developed and deployed ways to infect whole Chinese cities with diseases such as the bubonic plague and typhoid, among other horrifying activities.

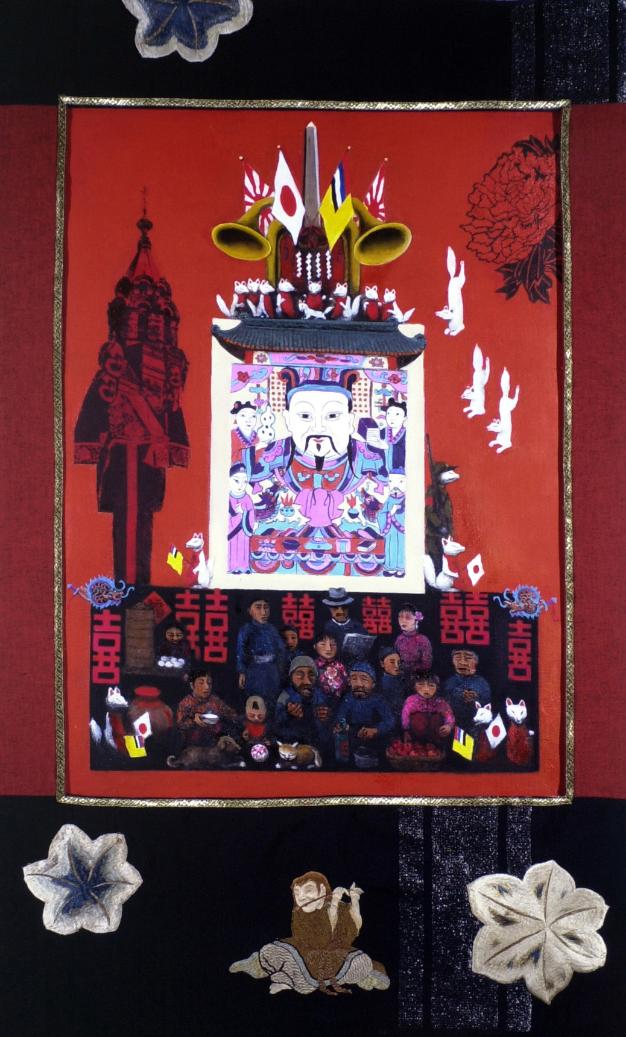

Tomiyama also started using the internet at that time, for example finding a photo of An Jung-Geun, the Korean patriot who famously assassinated Ito Hirobumi, the first Japanese colonial ruler of Korea, which she incorporated into a collage depicting six postcards of Harbin Station, the site of the murder. (He appears in the 1909 postcard.) Tomiyama’s cultural mixing through her collage techniques complements her focus in the Harbin series on the multicultural architectural and artistic heritage of Manchukuo, and the moral self-deceptions worked there.

The painting “Nostalgia for Days Gone By” reminds viewers that, despite the many changes in Japan since 1945, expressions of nostalgia for this particular past are a potentially dangerous step back into past attitudes.

See Yuki Miyamoto, “Fire and Femininity: Fox Imagery and the Ethical Imagination” and Laura Hein, “Post-Colonial Conscience: Making Moral Sense of Japan’s Modern World” in Laura Hein and Rebecca Jennison, eds., Imagination Without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility, Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan, 2010.

The Digital version is fully and freely accessible on the University of Michigan Press website.