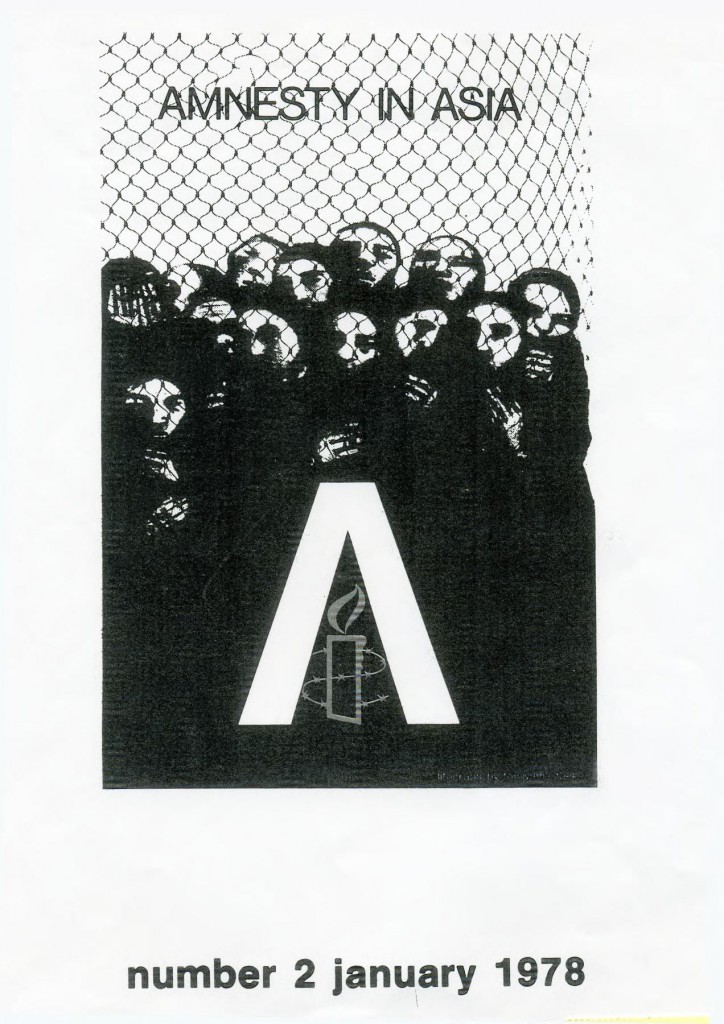

In the early 1970s Tomiyama began working with the international movement to support Korean prisoners of conscience organized by Amnesty International. During the Cold War, the Korean peninsula was—and remains—one of the most volatile places in the world.

Tomiyama’s activism on behalf of the Korean democracy movement was partly motivated by her understanding that U.S. support for both the South Korean and Japanese governments made them less accountable to their own populations, creating a regional geopolitical structure that not only discouraged democracy but also increased the likelihood of another devastating war. She was also aware that, not only had Korea been Japan’s colony up to 1945, but also the postwar “Korea war boom” that had brought temporary prosperity to Japan’s coal mines and boosted over-all economic growth in Japan was built on the suffering of Koreans.

Especially after the Communist Party won control of China in 1949, the Americans supported a series of extremely repressive regimes in South Korea, fearing that democratization would encourage communism. Backed by the United States, the South Korean government refused to meet the demands of its citizens for democracy, instead responding by imprisoning, torturing, and even executing its critics. While the postwar Japanese government was far less brutal toward its own population, it too supported the Korean government and also the American war in Vietnam, even though Japanese public opinion was overwhelmingly against that war.

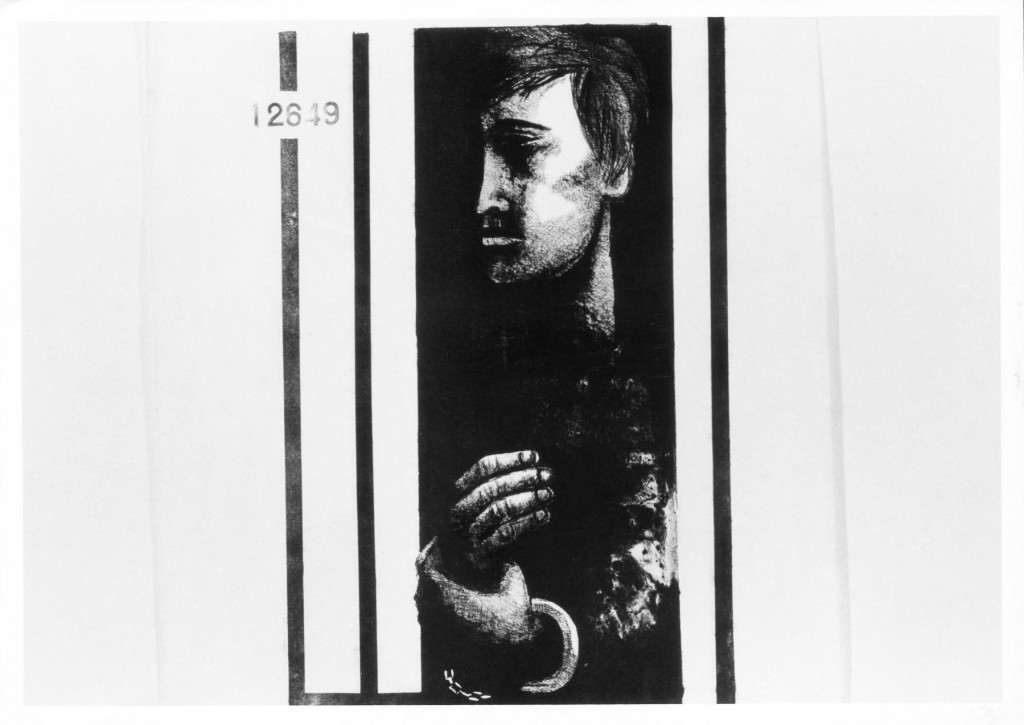

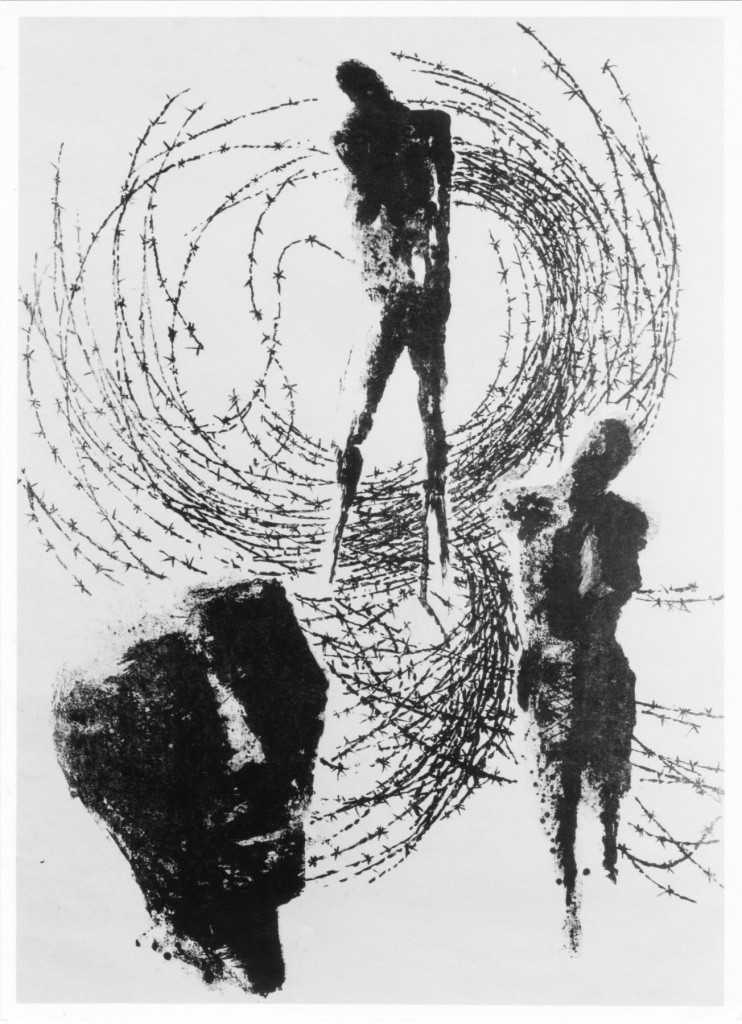

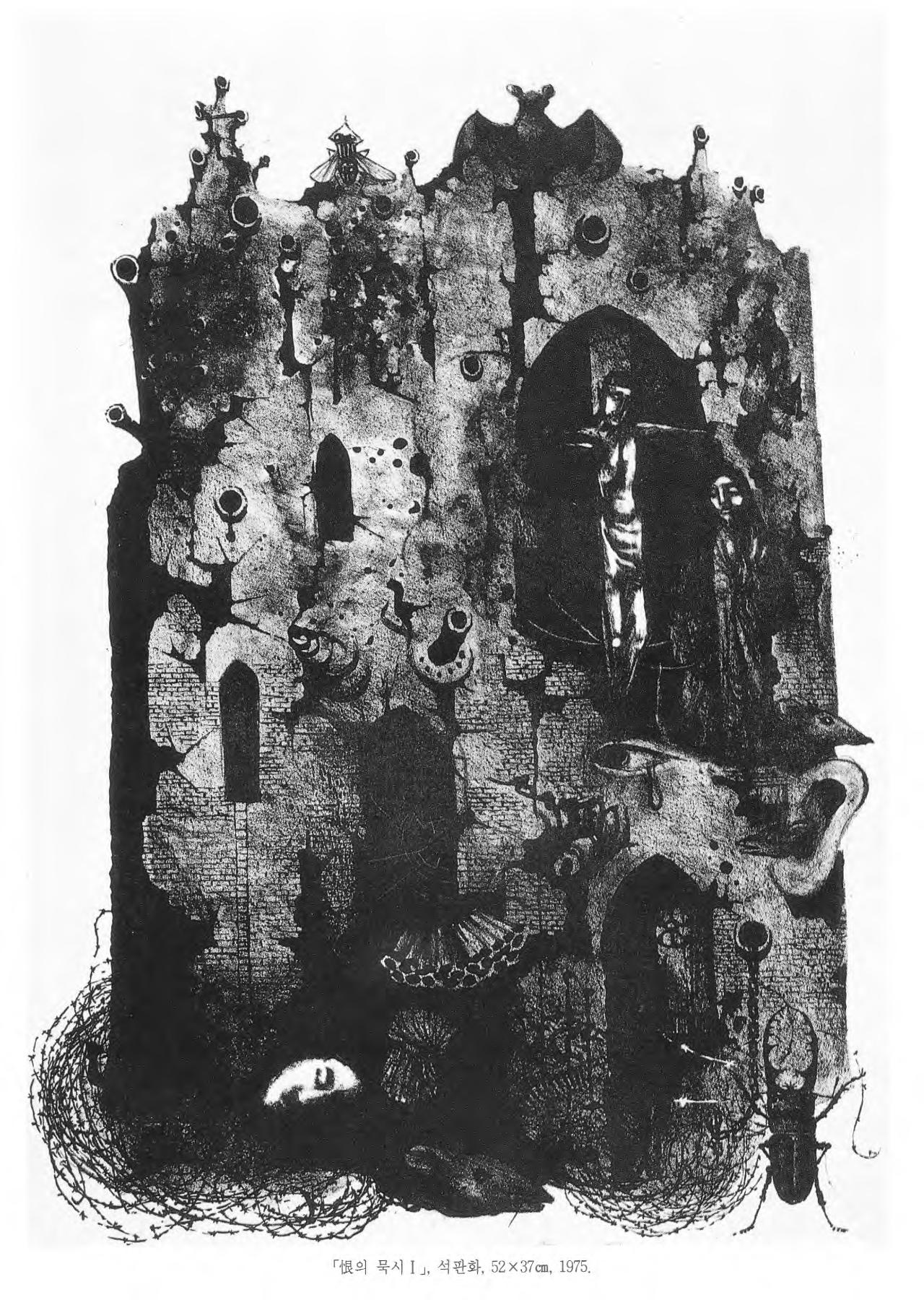

Tomiyama produced several series of lithographs supporting Korean political prisoners, including illustrations for a Japanese translation of a volume of poems by Kim Ji-ha, Korea’s most famous contemporary poet and political prisoner. These showed bold black-and-white figures trapped in tightly confined spaces. In a new direction for her work, her images of birds, butterflies, and silhouetted people penned in by coils of barbed wire simultaneously convey resiliency and fragility. The lithographs of ruined buildings and imagined landscapes she created for Kim’s poetry also foreshadow her later work in oil paint and collage. After this, Tomiyama created a similar series of lithographs commemorating the massacre of peaceful demonstrators in Gwangju city by the South Korean Army in 1980.

Tomiyama also turned to new methods for making her work accessible to a wider audience. Japan’s public television network, NHK, filmed a documentary about Kim Ji-ha’s life and poetry, which featured Tomiyama’s lithographs. Shortly before it was to air, however, NHK abruptly cancelled the show, probably because of pressure from the Japanese government. In response, Tomiyama created a slide show of her lithographs, Chained Hands in Prayer: Korea (1975) and her friend, Takahashi Yūji composed music to accompany it. The stand-alone artwork was transportable and simple to recreate if damaged. She then toured with it, meeting human rights groups both in Japan and internationally. As with earlier international travels, these interactions led to new ideas for future work.

See Hagiwara Hiroko, “Working On and Off the Margins” and Ann Sherif, “Art as Activism: Tomiyama Taeko and the Marukis” in Laura Hein and Rebecca Jennison, eds., Imagination Without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility, Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan, 2010.

The Digital version is fully and freely accessible on the University of Michigan Press website.