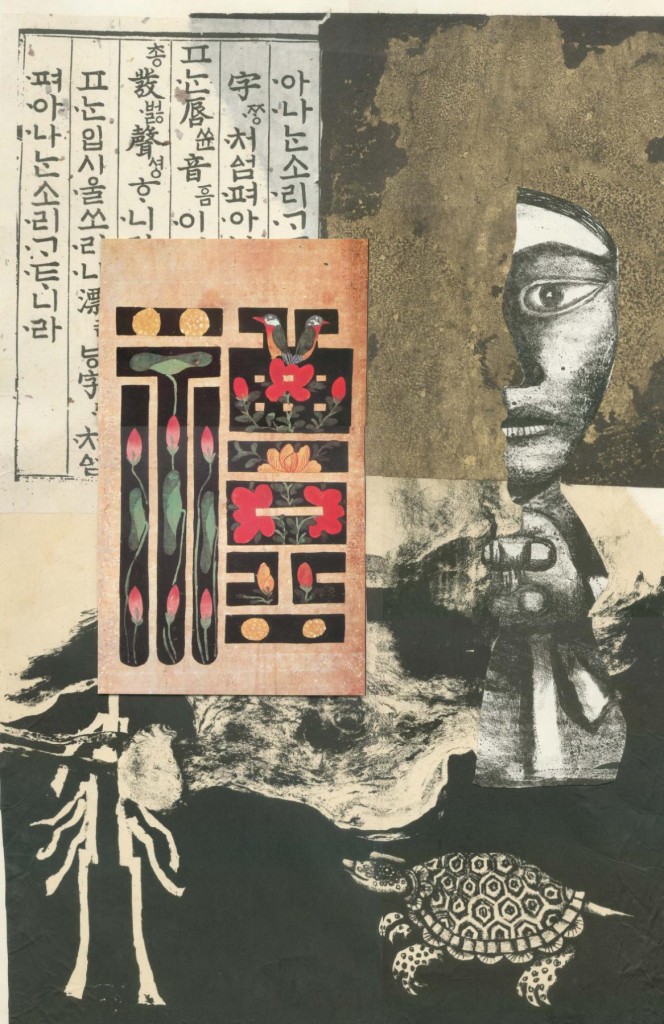

IMAGINATION WITHOUT BORDERS introduces the work of Japanese visual artist Tomiyama Taeko and, to a lesser extent, the paintings and prints of Maruki Toshi & Maruki Iri and Eleanor Rubin. All four think of themselves as political artists and see their work as a protest against social injustice and the suffering such injustice causes. All four were deeply affected by World War II and their art reflects their shared belief that war is a disaster for everyone.

This website was originally created to accompany a 2010 book, Imagination Without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility, University of Michigan East Asia Center Press, edited by Laura Hein and Rebecca Jennison. As of 2020, this book is freely and publicly available on line through the Michigan Asian Studies Open Access Books Collection, sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

My introduction in the book is intended as a starting point for that project, but the individual web pages here are also keyed to specific chapters of that book. While both book and website stand alone, the book provides far more analysis and detailed information than is presented here. The website, meanwhile, can offer many more images and demonstrate Tomiyama’s vibrant use of color far more effectively than is possible in all but the most expensive art books. Since Tomiyama is also committed to making her images accessible to a wide audience, for example by innovative use of slides and DVDs, incorporating the World Wide Web seems very much in the same spirit.

Both Tomiyama and Rubin have continued to produce new art since 2010 when we created this website. They were each moved to do so as a response to the triple disaster of the earthquake-tsunami-nuclear meltdown in northeastern Japan on March 11, 2011. While most of this website remains as it was in 2010, we have expanded it to include some of this new work and made it more accessible to Japanese-language readers as well. In 2020, we added Korean-language capacity to the website, to coincide with a Korean spike of interest in Tomiyama and her work on behalf of dissidents in the Republic of Korea in the 1970s and especially the Gwangju activists for democracy who were murdered in 1980.

Confronting the Meanings of the Asia Pacific War

Japanese today [in 2020] are still grappling with the effects of World War II, or the Asia-Pacific War, as that conflict is known in Japan. Largely because of the inconsistent and ambivalent actions of the government, Japanese today are widely seen as resistant to accepting responsibility for their nation’s violent actions against others during the decades of colonialism and war.

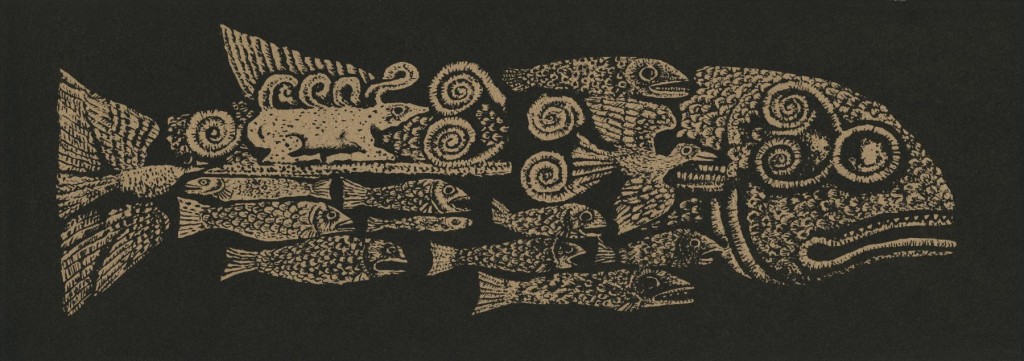

Yet some individuals have produced nuanced and reflective commentaries on those experiences. Tomiyama Taeko, born in 1921, is one such individual. Her art deals with complicated moral and emotional issues that cannot possibly be summed up in simple slogans, making it compelling for more than just its beauty. Her subject for the last quarter-century has been Japan’s colonial empire, its destructive wars in Asia, and their emotional and social legacies. It is also about the difficulty of disentangling herself from the priorities of the nation despite her lifelong political dissent. Tomiyama’s sophisticated visual commentary on Japan’s history—and on the global history in which Asia is embedded—provides a compelling guide through the difficult terrain of modern historical remembrance, in a distinctively Japanese voice. She asks why her generation of Japanese accepted such state policies as forced labor, organized sexual violence, and racially differentiated treatment of individuals. Tomiyama is particularly interested in exploring the complex ways that people can simultaneously be victims and perpetrators, sometimes in the same act. Rather than primarily trying to remember what was done to her, she wants to remember what she allowed to be done to others in her name but now regrets.

A significant intellectual and emotional journey is required whenever individuals come to reject activities and attitudes that they once accepted unquestioningly. In Tomiyama’s case, this transformation was intimately related to her development as an artist and her strategies of artistic expression. The more clearly she understood what she wanted to convey, the more powerful her images became. This is a major reason why Tomiyama’s most arresting work, including nearly all of her large oil paintings, appeared after age sixty-five.

Transnational Communities

Tomiyama has long been part of a community of like-minded people, first in Japan and later internationally, meaning that she did not make this journey alone. Two other Japanese painters, Maruki Iri and Toshi, most famous for their huge murals of Hiroshima after the atomic bombing, were friends and colleagues beginning in the early 1950s. Four of their images are included in this website to provide some of that context.

Tomiyama has always been energized by interactions with people outside Japan, particularly creative artists working in different media. She is drawn to politically engaged poets, and has cited the work of Romain Rolland, Pablo Neruda, Muriel Rukeyser, and Kim Ji-ha as particularly powerful influences. Like Tomiyama, these French, Chilean, American, and South Korean writers all tried to convey social protest through their art.

Tomiyama has also traveled abroad extensively, first spending a year in Latin America in the early 1960s and then visiting Central Asia, Southeast Asia, Taiwan, the United States, and both Western and Eastern Europe, including the Soviet Union. In the early 1990s she visited the Manchurian region of China, where she had lived as a teenager when it was a nominally independent country, under the control of the Japanese military. These trips provided her with new visual images and intellectual concepts that enriched her work. Her transnational contacts with labor-union, peace, and social-justice advocates in other parts of the world have consistently sparked Tomiyama’s imaginative breakthroughs, revealing the extent to which her creativity relies on escaping the confines of nationalism.

Tomiyama is also well-informed about international developments. She began thinking about expressions of responsibility for wartime actions, for example, after reading about West German Chancellor Willy Brandt’s gesture of apology on December 7, 1970 by kneeling before the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto uprising of 1943. It took another sixteen years before she found a way to translate his gesture into her art, suggesting the difficulty of the task. Her deepest hope is that her images trigger similar introspection in others.

In this spirit, the work of Eleanor Rubin, an American printmaker and watercolorist is included here. Her work deals with themes similar to Tomiyama’s, such as the discomfort that comes with believing that one’s own government is pursuing a cruel and unjust war. The two artists also share the experience of discovering feminism as adults, something that both women see as a deeply personal and self-affirming perspective, one that transformed the way they viewed the world. They also share some recurring images, such as faintly menacing birds.

This website, like the book it accompanies, lays out the historical and biographical context in which this art emerged but, like all successful creative endeavors, has the potential to open out in many different directions. Viewers are invited to engage with the images as they wish.

Laura Hein

Harold H. and Virginia Anderson Professor of Modern Japanese History

Northwestern University

September 2020