The Marukis, who were married to each other, are best known for their enormous joint paintings created between 1950 and 1982 that depict the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Like Tomiyama, they struggled with the problem of how to balance their commitments to their political beliefs with their artistic ideas, and how to think of themselves as Japanese who were critical of important aspects of their own society. (For more, please see the Maruki Gallery for the Hiroshima Panels.)

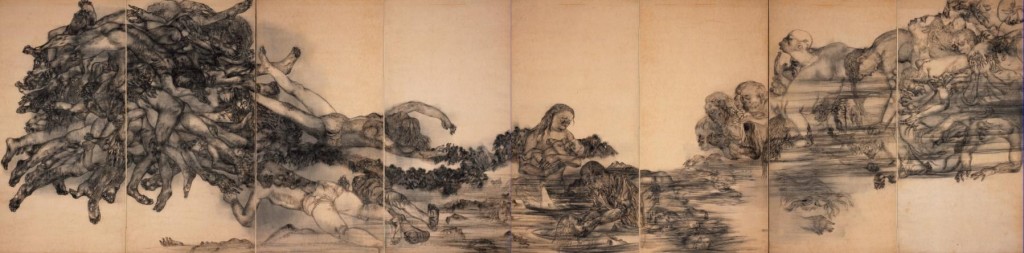

Both professional artists before 1945, Maruki Iri was trained in Japanese monochromatic ink painting (suibokuga), while Maruki Toshi focused on Western-style painting and book illustration. The two artists collaborated on their murals, sometimes painting right over each other’s work, creating something quite different from what each produced when working alone. These complex, densely layered canvases are mounted on screens. Their imposing presence is hard to approximate in the virtual environment.

The Marukis began painting the suffering of the people in Hiroshima because they had seen the aftermath themselves and were unable to forget it. Maruki Iri grew up in Hiroshima, and the couple rushed there a few days after the bombing to help the remnants of his family. Before long, though, creating the A-bomb paintings evolved into an activist project spanning several decades and garnering considerable domestic and international attention. The paintings express grief and profound sympathy for those who had experienced the bombings.

They also evoke beauty in subject matter generally considered to be unsuitable for aesthetic treatment. As Maruki Toshi explained, “We do paint dark, cruel, painful scenes. But the question is, how should we portray people who face such realities? We want to paint them beautifully.”

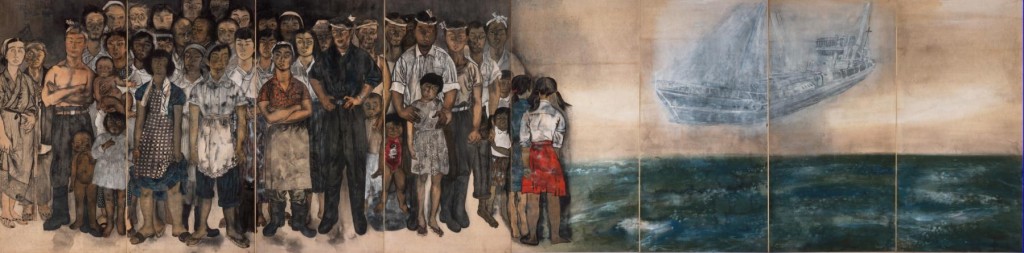

As time went on, the Marukis expanded their focus to consider nuclear issues more generally as well as Japan’s ethical and political responsibilities in the world. In the aftermath of the 1954 Bikini U.S. nuclear test, which spread radioactive fallout across the South Seas, contaminating a Japanese fishing boat (Lucky Dragon Number Five) and its crew, the Marukis painted the murals “Yaizu” (the name of the town where the fishing boat docked), which includes local people in a defiant stance, and “Petition” (1955, 1956). “Yaizu” extended their earlier criticism of American nuclear practice and highlighted Japan’s victimization. Indeed, when the Marukis first showed the “Yaizu” painting, they included an image of Mt. Fuji. After other Japanese leftists criticized them for naively invoking stereotypical “Japanese-y” imagery reminiscent of the bad old imperialist days, the Marukis removed Mt Fuji, replacing it with an image of the Lucky Dragon boat, as shown here. After this experience, the Marukis developed a more nuanced response to issues of national identity. They questioned the increasingly mainstream portrayal of Japan as an advocate for peace without any rejection of its own past deeds.

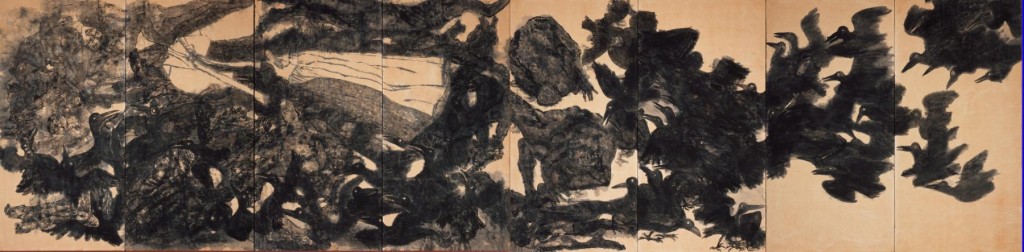

In the 1970s, the Marukis exhibited their paintings in the United States for the first time, an experience that had a huge impact on them. After an American viewer asked why they only painted Hiroshima and not incidents in World War II in which Japan was the aggressor, they widened their perspective to do just that, in two ways. The first was to acknowledge the moral complexity of the atomic bomb experience itself. Their 1972 painting, “Crows” refers to the severe discrimination Koreans faced in Japan, even in the immediate aftermath of the atomic bombings, when one might imagine that shared disaster would diminish prejudice against other sufferers.

After their American tour, the Marukis also expanded their subject matter to the horrors of war, not just atomic bombs. The results included “The Rape of Nanjing” of 1975, which depicted terrible acts that Japanese former soldiers had described to them. Like Tomiyama, they began to push for a repudiation of these and other wartime actions by their compatriots and the Japanese government.

This discussion draws on Ann Sherif “Art as Activism: Tomiyama Taeko and the Marukis” in Laura Hein and Rebecca Jennison, eds., Imagination Without Borders: Feminist Artist Tomiyama Taeko and Social Responsibility, Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan.

The Digital version is fully and freely accessible on the University of Michigan Press website.